While the early 90s Yankees struggled in many ways, one position they perpetually struggled to fill was third base. In the mid 80s Mike Pagliarulo capably filled the position, producing above-average offensive numbers for his first four years in the bigs. But his production dipped considerably in 1988, and the Yanks traded him the following year. They then struggled to fill the position*, inserting decidedly below-average hitters such as Mike Blowers, Randy Velarde, Pat Kelly, and even a utility player named Jim Leyrtiz. They clearly needed an upgrade at the position.

*For some reason, Velarde was a somewhat beloved player among kids from my generation. I’m fairly certain it’s because he hit .340 in 1989, after the Yanks had traded Pags. While he did perform a bit better in the mid 90s, I definitely remember thinking he was good in the early part of the decade, despite his actually horrible performance.

In 1991 the position hit something of a low mark. The Yankees started the season using 26-year-old Mike Blowers and 25-year-old Torey Luvullo, but both performed horribly. Jim Leyritz got some reps there, but not many (only 91 PA on the season). Eventually they settled on 23-year-old rookie Pat Kelly, a second baseman blocked by Steve Sax. Overall their third basemen produced a 65 OPS+ in 1991, 13th in the AL and far closer to the basement than to 12th. While pitching was clearly the priority during that period, an upgrade at third base was absolutely necessary.

For most of the off-season it was unclear what the Yankees would do at third. Luvullo’s performance put him out of the picture; he spent all of 1992 in Columbus before being granted free agency. They had traded Blowers during the 1991 season (for a player to be named later). The spot appeared to be Kelly’s again, but in early January they shipped Sax to Chicago, leaving second base open for Kelly. It seemed that Velarde was the starter by default. But two days before the Sax trade, the Yankees made a trade that would later net them their third baseman for 1992. They traded Darrin Chapin, whose name I vaguely remember, to Philadelphia for a player to be named later. More than a month later, after pitchers and catchers reported, the Phillies sent Charlie Hayes to the Yankees.

(Apparently the holdup was a technicality. The Yankees didn’t have any open spots on the 40-man roster, and so they held off on officially announcing Hayes. They eventually designated Alan Mills for assignment.)

If the internet had been around at the time of the trade, we’d have thought little of it. Hayes was a largely unremarkable third baseman. He had been the Phillies starter for the previous two and a half seasons, following a trade from San Fran. In his career he had produced a .276 OBP and a 78 OPS+. Still, that was an improvement over what the Yankees had thrown out there in previous years. The position wasn’t his to lose, though; Hensley Meulens was in the running for the job. Their competition lasted all spring, with Hayes emerging as the winner at the very end. Muelens spent the season playing third at AAA.

If the internet had been around at the time of the trade, we’d have thought little of it. Hayes was a largely unremarkable third baseman. He had been the Phillies starter for the previous two and a half seasons, following a trade from San Fran. In his career he had produced a .276 OBP and a 78 OPS+. Still, that was an improvement over what the Yankees had thrown out there in previous years. The position wasn’t his to lose, though; Hensley Meulens was in the running for the job. Their competition lasted all spring, with Hayes emerging as the winner at the very end. Muelens spent the season playing third at AAA.

Hayes turned out to be a revelation. His overall numbers might not have looked impressive — .257/.297/.409, a 97 OPS+ — but he represented a massive improvement over the previous years’ third basemen. With some quality backup work from Velarde and Leyritz, the Yankees moved from 13th to 4th in offensive production from third base, posting a combined 107 OPS+ at the position. That went along with an overall five-win improvement over 1991, a success for Buck Showalter in his first year at the helm.

I remember growing attached to Hayes that season, probably because he was simply so much better than his predecessors. I had only vague memories of Pags, and most of them were of his fading production in the late 80s. I had been used to dreck, so watching someone serviceable was quite the thrill. It came as a great disappointment, then, when I read the newspaper on November 18th, 1992. Major League Baseball had just held an expansion draft for the Colorado Rockies and the Florida Marlins, and the Rockies selected Hayes with their third pick.

Less than a month later, though, I had forgotten all about Hayes. On December 15th the Yankees signed Wade Boggs to man the hot corner. This was exciting not only because he was Wade Freaking Boggs, but because he was my best friend’s favorite player. (Despite my best friend being as die-hard a Yankee fan as I was at the time.) Lo and behold, Boggs, even at age 35 and coming off a colossally disapointing season, delivered the first above-average performance for a primary Yanks third baseman since Pags in 1987. You’d think Hayes would have become an afterthought, but that was not the case.

As it turns out, 1993 was a career year for Hayes. He played in 157 games for the fledgling Rockies, and he belted out a league-leading 45 doubles at Mile High Stadium. He ended the season with a .305/.355/.522 line, thereby producing his first season with an OBP over .300. He played in only 113 games the next season, with a .348 OBP but a bit less power. It was still better than almost any other season in his past. After the 1994 season he reached free agency, signing back on with the Phillies, where he produced essentially average numbers. Yet again, though, he produced a .340 OBP.

Before the 1996 season Hayes found a job with the Pittsburgh Pirates. Maybe it was the change of parks that killed his numbers, but he was pretty terrible through most of August, producing a .301 OBP and a 73 OPS+. Then, just days before the waiver trade deadline on August 31st, the Pirates flipped him to the Yankees for a guy named Chris Corn. Hayes got some playing time down the stretch, though he performed at less than optimal levels — essentially, he had turned back into his pre-1992 self for the whole 1996 season. He also did a whole lot of nothing in the playoffs, going 5 for 28, all singles, with three walks.

Before the 1996 season Hayes found a job with the Pittsburgh Pirates. Maybe it was the change of parks that killed his numbers, but he was pretty terrible through most of August, producing a .301 OBP and a 73 OPS+. Then, just days before the waiver trade deadline on August 31st, the Pirates flipped him to the Yankees for a guy named Chris Corn. Hayes got some playing time down the stretch, though he performed at less than optimal levels — essentially, he had turned back into his pre-1992 self for the whole 1996 season. He also did a whole lot of nothing in the playoffs, going 5 for 28, all singles, with three walks.

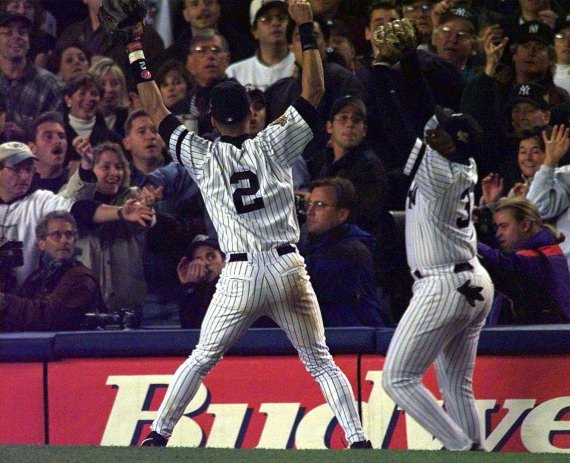

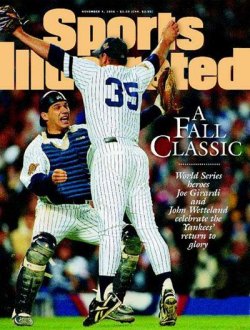

Of course, most of us most prominently remember Hayes for a single moment during those 1996 playoffs, his catch to end the World Series. Odd how that works. A guy who did absolutely nothing for the team during the season and in the postseason gets featured on every highlight reel. But we’ll all remember that moment, and so we’ll all remember Hayes.

He did stick around for the 1997 season — he had apparently signed a four-year deal with the Pirates — and in 398 PA he hit .258/.332/.397, a 90 OPS+. After the season, however, the Yanks planned to move in a new direction, and once again Hayes was involved in a funky player to be named later scenario. In early November the Yankees unloaded Kenny Rogers on the A’s for a player to be named later. On November 17th they dealt Hayes to the Giants, and then the next day they received Scott Brosius as the player to be named from Oakland.

In many ways, Hayes represented the plight of the early 90s Yankees. Here was a decidedly below-average player who represented an improvement. When he came in and produced almost-average numbers, it was a revelation. It was actually disappointing to see him go after the season, though the Wade Boggs acquisition headed that wound pretty quickly. And then, in his return trip, he turned in a performance that in no way could be described as remarkable, yet he’s front and center in one of the most iconic moments in recent team history.

And that, my friends, is the ballad of a man they call Charlie Hayes.

A previous version erroneously cited Coors Field as the Rockies’ home in 1993.