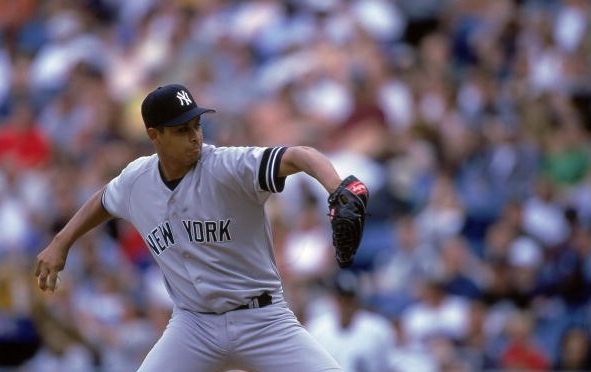

By any measure, Mariano Rivera is the greatest pitcher to ever come out of Panama. Arguably the second best pitcher from the country was Rivera’s teammate from 1996 through 2002, right-hander Ramiro Mendoza. The Yankees signed Mendoza as an amateur free agent in November 1991 — nearly two years after signing Rivera — and he gradually climbed the minor league ladder while receiving little fanfare.

As a 21-year-old, Mendoza posted a 2.78 ERA in 71.1 innings in 1993, most with the team’s rookie ball affiliate in the Gulf Coast League. The Yankees jumped Mendoza to High-A Tampa the next season, where he had a 3.01 ERA in 134.1 innings. One year later, he had a 3.13 ERA in 103.2 innings split between Double-A Norwich and Triple-A Columbus. In just three pro seasons, Mendoza had climbed six levels of minor league ball and put himself on the MLB map.

The Yankees sent Mendoza back to Triple-A Columbus to start the 1996 season but called him up when a starter was needed in May. On May 25th, the then-24-year-old Mendoza made his MLB debut in Seattle, holding the Mariners to three runs in six innings. It all went downhill after that. Mendoza allowed four runs in 3.2 innings against the Angels four days later and 25 runs in 26.1 innings in the month of June overall.

Following a five-run, two-inning disaster against the Red Sox on July 15th, Mendoza was sent back to the minors. “It was tough for him to gain confidence this way. He’s got big league stuff. He will be a big leaguer. It’s just a matter of time,” said manager Joe Torre to reporters after the demotion. Mendoza had an 8.05 ERA in 38 innings at the time. He pitched well in Triple-A (2.51 ERA in 97 innings) before resurfacing as a September call-up.

The Yankees did not carry Mendoza on their postseason roster in 1996 but he did make the Opening Day roster in 1997. Well, sorta. Mendoza won the fifth starter’s job in Spring Training but scheduled off-days allowed the team to skip his first two starts, so he started the year in Triple-A to stay sharp before making his season debut on April 13th, in the team’s 11th game of the year. He allowed six runs in 4.2 innings against the Athletics.

Mendoza had a 7.08 ERA in his first four starts of the season before settling down and firing three straight strong starts in mid-May. More importantly, his teammates were impressed. ”I don’t think anybody’s questioning (if he’s an MLB caliber pitcher),” said Paul O’Neill to Malcolm Moran. ”He had a great Spring Training this year. He’s not a guy that’s going to blow people away or a guy that’s going to be on Rotisserie League teams. He’s going to throw strikes, and he’s not going to be scared. You can see that when he takes the mound.”

Although he opened the year as the fifth starter, Mendoza was simply keeping the spot warm all season for Doc Gooden, who was coming back from hernia surgery. Mendoza moved into the bullpen in June and took over as the team’s do everything guy, pitching in short relief, long relief, mop-up situations, high-leverage spots, you name it. He made relief appearances as short as two batters faced and as long as 21 batters faced. Mendoza did it all.

Ramiro finished his first full big league season with a 4.24 ERA (106 ERA+) in 133.2 innings across 15 starts and 24 relief appearances. He earned the win with 3.1 scoreless innings of one-hit ball in Game One of the 1997 ALDS against the Indians and took the loss in Game Four when he allowed a walk-off single to Omar Vizquel. The Yankees dropped the series in five games. It was a disappointing season for the team but a successful one for Mendoza, who established himself as a big leaguer.

Mendoza again worked as a swingman in 1998 — he started the season in the rotation but eventually lost his spot when David Cone got healthy and Orlando Hernandez debuted and dominated — and had his best season, pitching to a 3.25 ERA (137 ERA+) in 130.1 innings. He started 14 games and came out of the bullpen 27 times. In three postseason appearances, he allowed one run in 5.1 relief innings as the Yankees won their second World Series title in three years.

Although he was in role short on glamour, Mendoza had entrenched himself as a valuable piece of the pitching staff and carved out a spot in Torre’s Circle of Trust™. ”He’s versatile, he throws strikes, he’s durable and he’s never had any arm problems,” said VP of Baseball Ops Mark Newman to Buster Olney in 1998. Other clubs began to notice him too — the Yankees declined to part with Mendoza in trade talks for Randy Johnson and Chuck Knoblauch.

From 1996-98, Mendoza had a 4.26 ERA (107 ERA+) in 317 innings despite striking out only 4.9 batters per nine innings, well short of the league average. If Rivera was a one-trick pony with his cutter, Mendoza was a one-trick pony with his sinker, which he used to get 1.87 ground ball outs for every one fly ball out from 1996-98. Here’s Olney on Mendoza’s sinker:

Mendoza generates sinkers by cocking his wrist, with his index finger and middle finger gripping the ball along the seams, and then snapping his wrist and fingers at the instant of delivery, like a buggy whip, and the ball spins with unusual alacrity.

Cone thinks Mendoza’s relatively long fingers create the additional torque; Newman theorizes that it could be the flexibility of Mendoza’s wrist — ”He has absolutely no stiffness” — or any number of factors.

Mendoza learned the sinker in the minors and initially wanted to scrap the pitch because it moved so much he was unable to control it. His pitching coaches and managers made him stick with the pitch and eventually he was able to locate it properly.

Because the Yankees had a stacked rotation in the late-1990s, Mendoza’s appearances as a starter became more and more limited. He started only six games in 1999 and nine games in 2000, then only two in 2001 and none in 2002. He had a 4.28 ERA (111 ERA+) in 189.1 innings from 1999-2000 and slightly improved his strikeout rate to 5.2 strikeouts per nine innings. From 2001-02, he had a 3.60 ERA (124 ERA+) in 192.1 innings and boosted his strikeout rate to 6.1 per nine.

The Yankees left Mendoza off their ALDS roster in 1999 but added him for the ALCS, in which he retired all seven batters he faced. That included recording the final five outs in the decisive Game Five, which the Yankees won 6-1 to take the series four games to one.

At age 30, Mendoza qualified for free agency after the 2002 season, and he made it clear he wanted to return to the Yankees. “I want to die here,” he told Tyler Kepner on locker clean out day. MLB implemented the luxury tax system after the season, however, and the Yankees were being careful with their money during the 2002-03 offseason. They wanted to make sure they had enough payroll space to sign Jose Contreras and Hideki Matsui, specifically.

Mendoza wanted a multi-year contract. Instead, the Yankees declined to offer him arbitration, meaning they were not allowed to negotiate with him until May 1st of the 2003 season. So, rather than die in pinstripes, Mendoza took a two-year contract worth $6.5M from the Red Sox just before the New Year. He had been on the disabled list at least once each year from 2000-02, so Boston made sure to check him out physically before agreeing to the contract.

“We’re very happy to have him in our bullpen,” said Red Sox GM Theo Epstein to the Associated Press. “Before the process even started we gave him a thorough physical in Fort Myers. He had MRIs on his shoulder and his elbow and he checked out extremely well. We had no reservations whatsoever. It was important we made sure he was healthy before making this kind of commitment.”

Mendoza held up physically in year one of his new contract but was a disaster on the mound — he had a 6.75 ERA (69 ERA+) in 66.2 innings spanning five starts and 32 relief appearances. A knee injury sidelined him for a big chunk of time in the middle of the season, and, aside from Game 162 after the team had clinched, manager Terry Francona did not once use Mendoza when the score was separated by fewer than seven runs (!) after July. Understandably, he was left of the postseason roster.

Offseason shoulder surgery and subsequent inflammation kept Mendoza out until mid-July in 2004, and although he put up a strong 3.52 ERA (138 ERA+) that year, he only threw 30.2 innings, easily the fewest of his career. Mendoza appeared in two postseason games for the Red Sox, allowing one run in two innings against the Yankees in the ALCS. Boston let him walk after the season, after Mendoza gave them 97.1 innings with a 5.73 ERA (83 ERA+) during his two-year contract. He was he original Embedded Yankee.

The Yankees gave Mendoza a minor league contract during the 2004-05 offseason but he spent most of the season hurt, appearing in only 17 minor league innings. The team did call him up in September and he made his only big league appearance of the year — and the final appearance of his career — on September 1st, when he allowed two runs in one inning. His MLB career started in Seattle against the Mariners and it ended there as well.

Mendoza did not pitch at all from 2006-08 though he didn’t retire either. He was on Panama’s roster for the 2009 World Baseball Classic and allowed five runs (two earned) in four innings in his only appearance, a start. Mendoza signed a minor league contract with the Brewers after the tournament but failed the physical. He instead spent that summer in independent ball, putting up a 3.83 ERA in 87 innings across 15 starts and two relief appearances for the Newark Bears.

Three years later, Mendoza again pitched for Panama in the World Baseball Classic, throwing 8.2 scoreless innings in three relief appearances in the qualifying round during the 2012-13 offseason. Just three offseasons ago, at age 40 and nearly a decade removed from his last MLB appearance, Mendoza still had his sinker working in the 2013 WBC qualifiers:

Baseball is a team sport though, and someone has to do the thankless dirty work. Mendoza was a thankless dirty worker from 1996 through 2002. He started, he relieved, he soaked up innings, and he received no accolades for being reliable and trustworthy. By swingman standards, Mendoza was as good as it gets.