Hat tipping both Tim Armstrong and Sean McNally for the title inspiration.

Last night’s game was infuriating for many reasons. We could spend hours griping about every individual failure, but how productive is that? Instead, I want to examine one aspect of the game, one that has recurred many times this season. In a situation that did not call for it, the Yankees chose to sacrifice bunt. It’s not the reason they lost the game; it actually ended up working. But in that specific situation, and in all situations from a general standpoint, sacrifice bunting does not represent sound strategy.

After blowing a one-run lead late in the game, the Yankees found themselves in extra innings. The Royals wasted little time in taking a 1-0 lead, which put the Yanks on the hot seat in the bottom of the 10th. It was hotter, still, because Joakim Soria was on the mound for Kansas City. In the past few years he has established himself as a premier closer, perhaps the best in the league after Mariano Rivera. But this year he has been hittable. It was clear from the first batter last night that he did not have his best stuff, as he walked Russell Martin on four pitches.

We all knew the sacrifice was coming. The Yankees have faced a number of situations this year where one run is of great benefit, and it seems as though Joe Girardi has deemed the sacrifice the correct move in every instance. Brett Gardner showed bunt on the first two pitches, but Soria missed with both. That was six straight balls. Even great pitchers have off nights, and the Yankees appeared lucky enough to catch Soria on one. So what did they do? They kept the bunt on, both on the 2-0 and 3-1 pitches. Gardner did get it down successfully, but to use the term success here is specious at best.

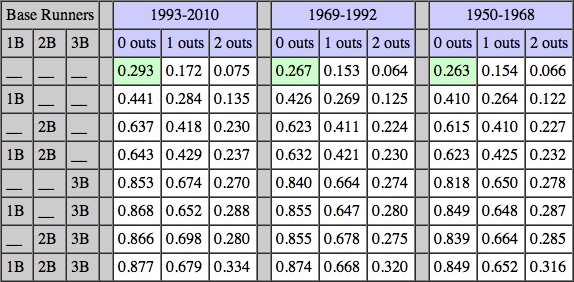

The problem with bunting in that situation starts with simple run expectancy. With a runner on first and no outs, a team has a 44.1 percent chance of scoring a run at some point in the inning. That’s not win expectancy, or multiple run expectancy. It is single-run expectancy. With a runner on second and one out, the chance they’ll score a run is 41.8 percent. The difference isn’t huge, but it does exist. Here is the entire table, for reference, courtesy of Tangotiger (with a hat tip to Capitol Avenue Club, the best Braves blog on the planet):

This is based on historical data, so we do have the true odds of something happening. Of course, when you take the average you have data points both above and below the average. In other words, there are individual instances where having a runner on second with one out is better for a team than a runner on first and none out. It’s up to the manager to pick and choose those situations and beat those odds. In this way I still see two issues with bunting here.

1) The Yankees had just three outs until death. This wasn’t a tie game, where yeah, it still matters, but failing to score in the inning won’t end the game. Either the Yankees scored or went home losers. Why, then, would you give away one of your chances when the odds say you have a worse shot in the new situation? Is Derek Jeter coming up with a runner on second and one out really better at this point than Brett Gardner batting with a runner on first and none out? I don’t think that specific situation mitigates the diminished odds. Gardner is going better than most guys on the team right now. Let him hit.

2) It was predictable. Picking your spots means doing it sometimes and not others. Everyone at the Stadium and everyone at home knew the bunt was coming. That makes it seem as though Girardi thinks that bunting is generally a good strategy in that situation. History says this is not the case. Again, you can beat the odds if you choose your spots wisely. But if your strategy is to consistently bet against the odds, you’re going to lose more often than not.

Of course, the bunt did work, in that Ganderson singled home Martin. Bad process can lead to good results, and even here the Yanks got incredibly lucky that Martin advanced to third on a Jeter grounder to short. There was no way Martin was scoring from second on Granderson’s single. Not with how hard he hit it, and not on Francoeur’s arm.

There is no reason to blindly hate bunts. There are situations when they can work out better than the alternative. But as a general strategy, history shows that they’re not sound. When a bunt means giving away one of your three remaining outs, it’s an even worse strategy. If Girardi is going to use it as an occasional ploy to gain an advantage, that’s one thing. But if he’s going to bunt in every one of these situations, it’s quite another. The evidence is not on his side.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.