While the Yankees teams of the 80s weren’t all bad — they did win more games than any other franchise that decade — they were flawed at many positions. One position they continually struggled to fill was catcher. It all started, unsurprisingly, with Thurman Munson’s death during the 1979 season. His replacements, Jerry Narron and Brad Gulden, couldn’t have performed much worse. From there the Yankees did better at the position, but it took nearly two decades to find a stable presence.

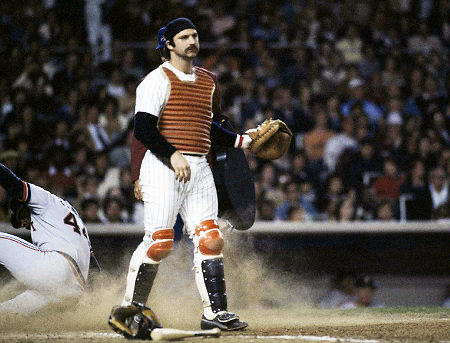

Knowing that their current options would not hack it for a full season, or even part of a season, the Yankees made a move after the ’79 season. They traded ALCS hero Chris Chambliss and two others to the Blue Jays for 26-year-old catcher Rick Cerone. In 1979 Cerone got his first taste of a starting gig, and while he was nothing special, he was light years better than Narron and Gulden. He stepped right in and caught 147 games for the Yanks in 1980, producing a career-best 107 OPS+ in 575 PA. Yet, as with most things Yankees in the 80s, the rest of the journey was downhill.

Knowing that their current options would not hack it for a full season, or even part of a season, the Yankees made a move after the ’79 season. They traded ALCS hero Chris Chambliss and two others to the Blue Jays for 26-year-old catcher Rick Cerone. In 1979 Cerone got his first taste of a starting gig, and while he was nothing special, he was light years better than Narron and Gulden. He stepped right in and caught 147 games for the Yanks in 1980, producing a career-best 107 OPS+ in 575 PA. Yet, as with most things Yankees in the 80s, the rest of the journey was downhill.

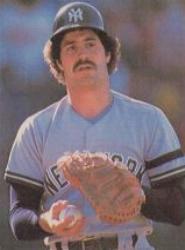

Injuries and ineffectiveness limited Cerone during the next four seasons, during which he started 278 games and hit .227/.271/.304 (63 OPS+) in 981 PA. That meant the Yankees would have to find other solutions during those years. While they wouldn’t find much in 1981 — their catchers produced a 79 OPS+, which was 12th out of the 14 AL teams — they did swing a trade early in the 1982 season that worked out fairly well. On May 12th they acquired Butch Wynegar from the Twins for three players whose names I do not recognize (Pete Filson, Larry Mulbourne, John Pacella). That’s probably because I was a month old at the time.

Wynegar exploded upon joining the Yankees, hitting .293/.413/.393 in 242 PA. In 1983 he played in 94 games and hit .296/.399/.429 in 357 PA. Injuries cost him some time in May and then again in early September, and those definitely hurt the Yanks. Cerone was still the backup, and he had a putrid season at age 29, a 52 OPS+ in 266 PA. Wynegar started for the Yanks in the next two seasons, and while they were good, especially for a catcher, they weren’t standout. By 1986 his production had faded, and after the season they traded him to the Angels for 20-year-old Alan Mills.

The Yanks didn’t let Wynegar’s fading production get them down in 86, though. The 90-win team also featured a spectacular half-season from the oft-traded Ron Hassey. The Yanks originally acquired him before the 1985 season, but then traded him to the White Sox in December, 1985. Strangely enough, the White Sox traded him back to the Yankees two months later, in February, 1986. After getting a superb half season out of him, the Yanks dished him at the 1986 trade deadline, back to the White Sox. They got in return Joel Skinner, a defensive specialist behind the plate. With the way he hit, he damn well better have been a defensive specialist.

This brings us back to 1987 and the Wynegar-less Yankees. After the 1984 season the Yankees had traded Cerone to the Braves, but in February, 1987, they re-signed him. He was coming off a halfway decent 1986 season for the Brewers, but he wouldn’t be quite so good for the Yankees in 87. He caught 113 games, which made it hurt even more. Still, it didn’t hurt nearly as much as Skinner’s OPS+ of 11 in 154 PA. To stanch the bleeding the Yankees swung a trade that June, sending 42-year-old Joe Niekro to the Twins for Mark Salas. That didn’t help much, as Salas produced a 58 OPS+. The Yanks would then send him to the White Sox after the season. The Yankees, apparently, had become the White Sox catching pipeline.

That was it for Cerone, at least that time around. The Yankees released him after spring training in 1988. Of course, he caught on the with the Red Sox and had two halfway decent seasons for them. At this point we reach my level of Yankees consciousness. I don’t remember the trade wherein the Yankees acquired Don Slaught for Brad Anrsberg, but I sure remember having Slaught’s baseball card that year. For the past few seasons Slaught had produced average numbers behind the plate while catching around 100 games per year. For a catcher that’s pretty solid production. He did pretty much the same for the Yankees in ’88 and ’89, adding offense where Skinner could not. That year we also saw the debut of Bob Geren.

That was it for Cerone, at least that time around. The Yankees released him after spring training in 1988. Of course, he caught on the with the Red Sox and had two halfway decent seasons for them. At this point we reach my level of Yankees consciousness. I don’t remember the trade wherein the Yankees acquired Don Slaught for Brad Anrsberg, but I sure remember having Slaught’s baseball card that year. For the past few seasons Slaught had produced average numbers behind the plate while catching around 100 games per year. For a catcher that’s pretty solid production. He did pretty much the same for the Yankees in ’88 and ’89, adding offense where Skinner could not. That year we also saw the debut of Bob Geren.

Before the ’89 season the Yankees traded Skinner to the Indians in exchange for Mel Hall. With Slaught producing well behind the plate, the Yanks could afford to ditch their no-hit catcher and give a bigger shot to Geren. The latter responded in 1989, hitting .288/.329/.454 in 225 PA. The Slaught-Geren combo produced the fourth-best offensive numbers for catchers in the AL. Apparently satisfied with the 27-year-old Geren, the Yankees traded Slaught after the season. That might have been a mistake. Slaught went on to produce a string of four more solid seasons for Pittsburgh, while the Yanks were stuck with nothing much at catcher.

To back up Geren in 1990, the Yankees signed — you guessed it — Rick Cerone. This time around it actually worked out decently; he produced a 99 OPS+ in 146 PA as the backup. But he was 36 years old at the time and couldn’t handle more playing time. Meanwhile, Geren was hitting terribly. That prompted a mid-season trade with the Tigers, wherein the Yankees acquired Matt Nokes. While Nokes had shown great promise as a 23-year-old in 1987, producing a 133 OPS+ in 508 PA, he had become a merely average hitter by the time of the trade. But, again, from the catcher position that’s valuable. Nokes hit well enough for the Yanks in 1990, but the best was yet to come.

Nokes took over the starting gig from Geren, and in 1991 he 112 games behind the plate for the Yankees, a big deal at the time. His average and OBP were nothing to write home about, .268 and .308, but he did sock 24 homers, leading to a 113 OPS+. As a 9-year-old Little League catcher, I loved Nokes. It helped that he bashed a long homer to right field, as I was sitting down the first base line, during one of the games I attended with my dad in 1991. Nokes followed up his ’91 performance with an average one in ’92, producing an OPS+ of exactly 100. After another average, if injury plagued, season in ’93, he ended up socking seven homers in 85 PA for the 1994 team. That, however, would end his time in pinstripes.

Nokes took over the starting gig from Geren, and in 1991 he 112 games behind the plate for the Yankees, a big deal at the time. His average and OBP were nothing to write home about, .268 and .308, but he did sock 24 homers, leading to a 113 OPS+. As a 9-year-old Little League catcher, I loved Nokes. It helped that he bashed a long homer to right field, as I was sitting down the first base line, during one of the games I attended with my dad in 1991. Nokes followed up his ’91 performance with an average one in ’92, producing an OPS+ of exactly 100. After another average, if injury plagued, season in ’93, he ended up socking seven homers in 85 PA for the 1994 team. That, however, would end his time in pinstripes.

Nokes was something of a sensation for young Yankees fans at the time. My only memories of Yankees catchers were Slaught, Geren, and a little Cerone, and none of them had any power. Nokes, on the other hand, simply mashed the ball. He hit more homers in 1991 than Geren hit in his entire career. Slaught hit 14 in his two years with the Yankees and topped 10 homer only twice in his career. Nokes? He led the Yankees in homers in 91 and finished just three behind team-leading Danny Tartabull in 92. All told he knocked 71 homers in 1510 PA for the Yanks from 1990 through 94.

In 1992 the Yankees had acquired another big bat catcher. Despite Nokes’ team-leading production, they signed Mike Stanley as a free agent. The two split time at catcher in ’92 — Stanley had never really handled the position full-time, and he responded by producing a 125 OPS+ in 207 PA. His role expanded in 1993, and he hit even better: a 150 OPS+ in 491 PA. That year the Yankees’ catchers were outhit only by Baltimore’s. That’s what happens when your starting catcher puts up a 1.001 OPS. Seriously.

Stanley served as the Yanks’ backstop during the strike-shortened 1994 season, again producing monster numbers. He was less awesome, but still solid, in 1995, his final season with the Yanks (that time around). After the season the Yankees let him go as a free agent, opting to go with a more defensive-minded, at least by reputation, catcher in 1996. Stanley signed on with the Red Sox, though he’d make his way back to New York in 1997. In what seems to be the last trade between the two clubs, the Yankees acquired Stanley from the Sox for Tony Armas. This is somewhat significant, because the Red Sox used Armas that off-season as part of a package to acquire Pedro Martinez.

It’s no surprise that the Yankees had a revolving door at the catcher position throughout the 80s and 90s. Catchers don’t typically last long, and when they do their teams tend to hang onto them. It’s not easy to acquire a good catcher, and even if you do it 1) costs a lot in a trade or free agency, and 2) might not work out, since catchers can break down at any time. Still, the Yanks particularly struggled when seeking stability at the position. They found a few bright spots along the way, but it wasn’t until Jorge Posada started breaking into the league in 1997 that they found their true replacement for Munson. All told, 20 years between star catchers isn’t that long a stretch.