It might be hard for the younger generation of fans to believe, but two decades ago the Yankees were a non-factor in the AL East, finishing no better than fourth in the then-seven team division from 1987 through 1992. They hadn’t been to the playoffs since 1981. Don Mattingly was a bonafide homegrown superstar, but Dave Righetti’s talent was being wasted in the bullpen, Ron Guidry was fading, and a numerous free agent signings and trades just didn’t work out. For every Dave Winfield there was an Andy Hawkins, for every Rickey Henderson a Tim Leary.

George Steinbrenner, who always dipped his toe deep into the baseball operations pool, was banned from day-to-day management of the team in late-July 1990 after paying Howie Spira $40,000 to dig up dirt on Winfield. Gene Michael took over as general manager the very next month, and he and his front office staff went to work rebuilding the Yankees without The Boss interfering. They were patient with prospects, valued high-end pitching, and above all wanted batters that worked the count and wore pitchers down.

One of the team’s few established above-average players was centerfielder Roberto Kelly, who broke in during the 1987 season but didn’t grab hold of an every day job until two years later. He hit .284/.339/.426 from 1989 through 1991, increasing his homer output from nine to 15 to 20 during that time. Kelly rode a hot start (topped out at .361/.396/.514 in late-May) in 1992 to his first appearance in the All Star Game, though ironically enough that ended up being the worst full season of his career (98 OPS+, 0.8 bWAR) up to that point.

The then-28 year old Kelly was obviously a solid contributor for the Yanks, but his on-base percentage (just .325 from 1990-1992) wasn’t good enough for a guy that spent the majority of his time hitting in one of the top three spots of the batting order. Eighteen years ago today, Stick dealt Kelly to the Reds for a fellow 1992 All Star outfielder named Paul O’Neill and Single-A first base prospect Joe Deberry.

O’Neill was more than a year older than Kelly and relegated to an outfielder corner defensively, but it didn’t matter. He fit the grind-it-out philosophy, not only getting on base 34.4% of the time from 1989-1992, but he was also trending upwards. His IsoD (isolated discipline, or OBP-AVG, which measures a batter’s ability to get on base by a means other than a hit) went from .069 in 1990 to .090 in 1991 to .100 in 1992. O’Neill also brought World Series experience, though he wasn’t without his warts. The lefty swinger had plenty of trouble against southpaws, hitting .225/.279/.295 off them in 1992, and just .227/.278/.332 over the last three seasons.

O’Neill’s first season in New York was the best of his career up to that point, a .311/.367/.504 effort, career highs across the board. He was still hopeless against lefties though, hitting just .230/.279/.319 off them that year. The Yankees improved by a dozen wins from the previous season and finished second to the Blue Jays in the division. O’Neill managed to top his strong debut season with a career year in 1994, winning the batting title and hitting .359/.460/.603 with more walks (72) than strikeouts (56) for the first time in his career. As if someone flipped a switch, he hit .305/.439/.571 off lefties and went to his second All Star Game, finishing fifth in the MVP voting. The Yanks were robbed of their first playoff berth in more than a decade because of the strike though; at 70-43, they had the best record in the AL.

As the Yankees incorporated more and more young players onto their roster, O’Neill remained one of manager Buck Showalter’s stalwarts. His newfound level of production proved to be his true talent level, as O’Neill hit a whopping .317/.397/.517 during his first six years in pinstripes. He was the three-hole hitter the majority of the time during the team’s titles runs in 1996, 1998, 1999, and 2000, usually protected by cleanup hitter Bernie Williams, the guy that replaced Kelly in centerfield after the trade.

All told, O’Neill hit .303/.377/.492 with 185 homers in his nine years with the Yanks, going to four All Star Games and finishing in the top 15 of the MVP voting four times as well. Steinbrenner, reinstated by the commissioner two years after being banned, dubbed him The Warrior, and fans fell head over heels in love with him for his style of play. O’Neill was famously hard on himself, throwing helmets and smashing water coolers whenever something went wrong, and if you took a gander at him in the outfielder between pitches or at-bats, you’d often catch him practicing his stance and swing with an invisible bat.

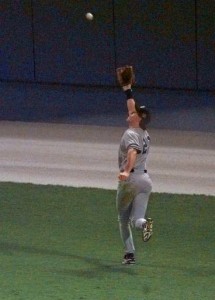

O’Neill’s Yankee career is full of far more memorable moments than I care to count, but two stick out to me. The first is pretty obvious, the “Paul O-Nei-ll clap clap clapclapclap” chant in the ninth inning of Game Five of the 2001 World Series, a grand send-off in his final game at Yankee Stadium. The second came back in 1996 (left), when he ran down a Luis Polonia line drive to record the final out of Game Five of that World Series, saving an extra-base hit in a game that ended 1-0. I’ll also never forget yelling at him through the TV to catch the final out of David Wells’ perfect game with two damn hands. Sheesh.

As for Kelly, he went on to be very productive for Cincinnati, hitting .313/.353/.447 for them before being traded to Atlanta for Deion Sanders during the 1994 season. He bounced around a bit the rest of his career, making stops with the Expos, Dodgers, Twins, Mariners, and Rangers before rejoining the Yankees in 2000, a 27 plate appearance finale to his career. He was certainly a quality player, just not at the same level of O’Neill. Deberry never played in the big leagues, topping out at Triple-A. He was out of baseball by 1998.

O’Neill’s 24.8 bWAR with New York is more than Kelly’s entire career (16.9, just 5.0 post-Yanks), but we don’t need any kind of advance stats or detailed analysis to call this trade a clear win for the Yankees. It’s arguably one the ten best trades in franchise history, maybe even top five. The Warrior is still a fan favorite and a semi-regular at Yankee Stadium to this day, showing up to Old Timer’s Day and calling games for the YES Network whenever he feels like getting out of Ohio.

Happy Paul O’Neill Trade Anniversary Day, I’m not sure any of us knew how important and beloved he’d become.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.