The following is a guest post from Adam Moss, who goes by Roadgeek Adam in the comments. He’s previously written guest posts on Tim McClelland, Frankie Crosetti, the No. 26, Casey Stengel, Leo Durocher, Miller Huggins, Jerry Kenney, the Copacabana incident, Mark Koenig, Earle Combs, Urban Shocker, Michael Milosevich, and Snuffy Stirnweiss.

Being a New York Yankee in 1943 was an unsure time. Most players knew it was inevitable that players would be drafted into the United States Armed Forces and serve abroad. By the beginning of the 1944 season, most players knew they were being drafted. Teams spent most of 1943 preparing for such a thing. The Yankees acquired players to replace bodies such as Buddy Hassett, Phil Rizzuto and Joe DiMaggio. As a result, 1944 had a lot of players win awards that no one would have picked. Hal Newhouser and Buddy Marion won the MVPs in their respective league that year. An outcast from the Philadelphia Athletics was a 1943 Yankees world champion and he is the subject of the story.

The Prussian Warrior

Nicholas Raymond Thomas Etten was born on September 19, 1913 in Spring Grove, Illinois, just off the Chain O’Lakes in McHenry County. His parents were Joseph Bernard (1883-1940) and Gertrude Mary Scheusen Etten (1883-1966). While little is known about his father’s family, there is quite the history behind his mother’s. Gertrude Mary Scheusen Etten is the granddaughter of Karl Ernst Du Sartz de Vigneul, a former member of the Prussian nobility. While the Du Sartz de Vigneuil nobility heritage came out of the Lorraine section of France, Dr. Sharon Koelling of Iowa State University noted that the family history dates back to the 17th century. Karl Ernst was disowned by the Prussian nobility when they disapproved of his marriage to a commoner, Catherina Niederprum.

A member of the Prussian Uhlan Regiment, Karl Ernst du Sartz de Vigneul was a warrior for the German cavalry in their military. After his death in the Rhineland city of Seffern in 1872, the widow Niederpaum and their nine children immigrated to Chicago, Illinois. One of their daughters, Anna Margaretha Du Sartz de Vigneul Scheusen was Gertrude’s mother. Gertrude was one of eight kids belonging to Du Sartz de Vigneul and Heinrich Scheusen. Nick Etten was one of three children for Joseph and Gertrude, with elder brothers Joseph Etten (1906-2004) and Hubert Etten (1908-1982) preceding him in birth.

Nick Etten on the right as a member of the St. Rita's of Cascia High School. (Suburbanite Economist, May 2, 1930). #Yankees pic.twitter.com/NivpMzaP4M

— Adam Seth Moss, M.A. (@LFNJSinner) November 24, 2017

Nick Etten was a three-sport star at St. Rita of Cascia High School in Chicago, located at 7740 South Western Avenue. There, he specialized in baseball, basketball and football. At St. Rita’s, he was a guard in basketball, a first baseman in baseball and right end for the football squad. Graduating from St. Rita of Cascia in 1931, Etten took his talents to Villanova University. However, at Villanova, he took his football talent to another level. Despite that football talent, Etten joined the Duffy Florals, a semi-pro team in Chicago during the 1932 season until Cletus Dixon, the manager signed him to a contract with the Davenport Blue Sox, passing up a four-year athletic scholarship at Villanova.

At age 19, Etten succeeded with the Class-B team in the Mississippi Valley League. In 114 games, he got 162 hits, 35 doubles, 4 triples and 14 home runs on his way to a .357 average and .544 slugging percentage for the Blue Sox. However, the Pittsburgh Pirates came calling for the Davenport outfielder in August 1933. At 6’1”, 195, he was a skinny player, and the Pittsburgh Pirates scout that discovered him, Carleton Molesworth, a former pitcher who appeared in three games in 1895 for the Washington Senators, thought that Etten’s speed was below average, something he would gain with experience. Molesworth considered him the best player prospect in the Mississippi Valley League and bought him from the team for more than $2,000 in cold hard cash.

Molesworth ended any intent of the outfield experiment continuing on from Davenport. During his time with the Blue Sox, Etten managed 12 errors in the outfield. The Pirates decided that Etten would move back to his main position of first base. Molesworth stated to the press that all opportunities would be made to get him to work out at first base. Molesworth was confident that Etten would be ready for the big leagues in two years and farmed him out appropriately. As part of the deal, Etten would stay with the Blue Sox through the end of the season, and the Mayor of Davenport, IA, George Tank presented the 19-year old with a traveling bag for joining the Pirates at Islander Field on September 11. Etten arrived at Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field on September 18, the day they announced the signing of shortstop Elmer Trappe.

During Spring Training in 1934 for the Pirates at Paso Robles, California, manager George Gibson worked with Etten every day to improve his work at first base. The Pirate team of 1934 was already loaded, with Floyd Young, Paul and Lloyd Waner and Freddy Lindstrom on the team. That Spring Training, Gibson worked with Etten specifically on how to go around first base without tripping on his legs in order to make plays. Gibson stated that his 6’1” inch frame made him perfect for first base and would be a good alternate if Gus Suhr had a slow start. On April 5, 1934, it was announced that Etten would be on his way to Little Rock, Arkansas to play for the A-team Travelers as a first baseman.

In 1934, the season with the Little Rock Travelers was the first sign of things going backwards. After a great season with Davenport in 1933, the Travelers got a player with only 120 hits, 22 doubles, 4 triples and 2 home runs in 113 games. His batting line fell to a .291 average and.379 slugging, and things only seemed to look worse in 1935. In 1935, he jumped from the Elmira Pioneers, Birmingham Barons and Oklahoma City Indians, he managed all of a .264/.379 line with 108 hits, 22 doubles, 2 triples and an uptick to seven home runs.

The 1936 season was the fix. Demoted to the B-league Savannah Indians, Etten hit .329 and got 162 hits, 28 doubles, 10 triples and 12 home runs. It was enough to re-promote him to the A-ball Wilkes-Barre Barons. However, the prospect glow was gone from Etten. He spent the entire 1937 season with Savannah, hitting .304/.518 with 156 hits, 27 doubles, 10 triples and then-career high 21 home runs. By now, Etten was playing in the outfield once again. In 1938, he started the season with the Jacksonville Tars of the South Atlantic (B) League after two years with Savannah. Out of the Pirates organization, Etten batted .370/.516 with 193 hits, 15 triples and 2 home runs (along with 40 doubles) in Jacksonville.

Damaged Goods

The Philadelphia Athletics came calling in 1938. On September 1, 1938, Connie Mack purchased his contract from the Sally League and he would join the team in the majors as a first baseman. Mack got Etten his first game on September 8 against the Washington Senators. It was an eventful debut as a brawl broke out that day between Billy Werber and Buddy Myer. After Myer performed a knockout slide of catcher Harold Wagner, Werber took it upon himself to tell Myer where he can put his slide. The two went to fisticuffs and the fight was on. Umpire Bill Grieve tossed both for the rest of the event.

The next day, Etten got his first hit against Jim Bagby and the Boston Red Sox in a 4-3 win at Fenway. With the A’s in 1938, he played in 22 games, going 21 for 81, getting 6 doubles, 2 triples and no home runs while batting .259/.333/.383. For 1939, he started the season with the Athletics, managing a .252/.322/.406 line in 43 games with 39 hits, 11 doubles, 2 triples and three home runs. His first home run was off Bump Hadley of the Yankees on April 25, 1939 at the Stadium. After the game on June 10, he was optioned back out to the AA Baltimore Orioles. With the Orioles, he played 105 games, getting 115 hits, 25 doubles, 3 triples and 14 home runs, batting .299/.490.

In 1940, the Baltimore Orioles fell under the guise of a Philadelphia Phillies affiliation. As a result, the Phillies acquired Etten. That year, Etten managed a .321/.530 batting line with 185 hits in 160 games with the Orioles. He also hit 4 triples and 40 doubles. The power was slowly being discovered by Etten. 1941 became the first season in which Etten did not have to join the minor league teams. As the starting first baseman for the Phils, Etten hit .311/.405/.454 with 14 home runs, 4 triples, 27 doubles and 168 hits in his first full season. That year he finished 28th in the MVP voting. Etten returned in 1942 with the Phillies, playing in 139 games, but showing a clear decline. Etten hit .271/.355/.420 with 121 hits, 21 doubles, 8 home runs and 3 triples.

First base for the New York Yankees had been a mess leading into the 1943 season. In 1941, the Yankees had a rookie first baseman named Johnny Sturm (#34) from St. Louis. Despite the World Series ring in 1941, Sturm enlisted in the United States Army and served in World War II. He never saw another MLB game. He managed to injure himself in a freak tractor accident trying to build an Army baseball field, damaging his right index finger. He tried for a comeback in 1946, but injured his wrist and finished in the minors the rest of his career. However, he was the man who first recommended the Yankees look at Mickey Mantle. In 1942, the Yankees replaced Sturm with Buddy Hassett, a former first baseman for the Dodgers and Braves. Hassett was a god complimentary piece in 1942, but he went to the war effort leading into the 1943 season. He never played another MLB game after serving in the minors until 1950.

With the need to replace Hassett, the Yankees acquired Nick Etten on January 22, 1943. In return, the Yankees sent the Phillies $10,000 along with pitcher Allan Gettel and first baseman Ed Whitner Levy. However, the trade was not without controversy. William Cox, the President of the Phillies, took issue with the fact that Levy and Gettel would not be with the Phillies in 1943. As a result, the Yankees took back Gettel and Levy and sent Tom Padden and Al Gerheauser instead to the Phillies on March 26.

1943 Yankees: Joe Gordon, Nick Etten, Snuffy Stirnweiss, and Billy Johnson. (Chicago Tribune, September 1, 1982). #Yankees pic.twitter.com/tkHrCe5I5G

— Adam Seth Moss, M.A. (@LFNJSinner) November 24, 2017

From Last to First

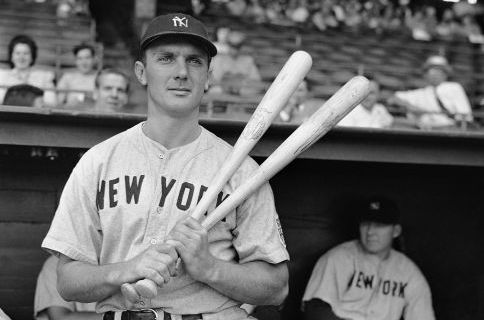

Leaving the dumpster bin Phillies did wonders for Etten. In his first season with the Yankees, batting seventh in the lineup, Etten took Joltin’ Joe DiMaggio’s #5 to a .271/.355/.420 line. He played all 154 games at first, getting 158 hits, 35 doubles, 5 triples and 14 home runs. He drove in 107 RBIs. In his only postseason opportunity, Etten had a miserable postseason, batting .105/.150/.105 in 19 at bats against the St. Louis Cardinals. Despite that, the Yankees won Etten his only ring in 1943. In 1943, he was one of four Yankees to finish in the top 10 of MVP voting. Spud Chandler won the award, Billy Johnson finished 3rd, Etten 7th and Bill Dickey 8th.

1944 was Etten’s time to shine. Coming into March, the Yankees expected that Etten would be the only member of the starting infield that would return for the 1944 season. However, in early March, during Spring Training, Etten, along with New York Giants star Mel Ott, were reclassified into Draft Class 1-A. Draft Class 1-A was the one that made people eligible for the draft. Manager Joe McCarthy noted that Etten was not expected to report until the summer for his examination.

However, the draft decimated the infield for McCarthy and the Yankees. Not only was Etten eligible, but Billy Johnson and Charlie Keller went to the Merchant Marines. During Spring Training, Bill Dickey was called to war and two days after Dickey, Joe Gordon went to war. Beat writers considered the race for the 1944 American League pennant as open as ever. McCarthy assembled a rag tag version of his infield to replace the ones fighting abroad: Etten at 1B, Snuffy Stirnweiss at 2B, Frank Crosetti and Mike Milosevich at SS, Oscar Grimes at 3B and a team of Mike Garbark and Rollie Hemsley at catcher.

Etten was on a torrid pace to start the 1944 season, heavily credited for keeping the rag-tag Yankees in the race for the pennant early on. By May 18, a month into the season, Etten hit a .354/.485/.494 line with 3 home runs and eight multiple hit games. By June 18, Etten had slowed to a crawl with his average falling below .300 on June 7. He also fell in the lineup. When the season started, McCarthy had Etten in the 3-hole. On April 30, when he was hitting well, McCarthy put him in the 4-hole. On June 11, McCarthy moved him to the 5-hole. He stayed there through the 4th of July, except for June 12 and June 13, when he was back in the 4-hole. For the four games after Independence Day, Etten went to the 6-hole. He never left 5th after that.

Late August and September 1944 were Etten’s best time for power. In a span of August 31 to September 16, the Yankees first baseman hit 6 home runs. From September 16 to September 27, Etten went on a 13-game hitting streak. However, Etten never saw .300 again, despite peaking on September 27 with a .297/.403/.474 batting line. After that, Etten’s bat went cold again, despite a 2 hit game on October 1. Etten’s final line: .293/.399/.466 in all 154 games.

The Yankees lost to the Browns and the Tigers in 1944 as the Browns went for the World Series and the Yankees went home. Despite that, Etten led the majors in home runs with 22. A feared power hitter, Etten led the league in walks (97) and intentional walks (18). He only had 4 triples and 25 doubles (numbers that went down from 1943). In day games (126), he hit .307/.420/.503; in night games (all of 28), he hit .236/.306/.309. Also a pure left-handed hitter, the splits were insane with a .308 average against righties and .235 against lefties. The 296 foot right field in Yankee Stadium benefited Etten enormously as he hit 15 of his home runs at home and 7 on the road. However, the splits between road and home in average were a lot more reasonable (.304 (home) and .283 (road)). Etten finished 23rd in MVP voting that season, tied with Rudy York.

1945 was a slightly backwards season, but not by much. His April and May 1945 were much the same as his April and May in 1944. Through May 18, Etten hit .321/.411/.500 as the starting first baseman. However, unlike 1944, the 1945 season did not fall off a cliff. Etten managed a .300 or higher batting average until July 1. During that streak, McCarthy put him back in the 4-hole. After a 4-hit game in Cleveland, Etten got his average back above .300, but it would not last. On August 25, Etten was put back in the 5-hole for good, and Etten finished the season with a .285/.387/.437 batting line in 152 games. However, in part due to his good season, he drove in a league-high 111 RBI with 18 home runs and 161 hits. Etten finished 1945 with a 15th place finish in the MVP race.

Statistically, 1945 was an unusual season for Etten, if compared to 1944. For a 1944 season where Etten looked bad against left-handed pitchers, his 1945 season is amazing. In 1945, he hit .333 against left-handed hitters versus .267 against right-handed hitters. At home versus away, he hit better away (.287) versus at home (.283). However, his power remained mostly at home (12-6). In another statistical flip, Etten hit .311 at night despite .281 at home (19-133 games ratio). It would be reasonable to say 1945 was his best overall season, despite the lowered power numbers. Either way, 1944 and 1945 were the best years of his career.

The End of Etten

1946 was another story. With the war effort over and Joe DiMaggio back, Etten switched to #9 and promptly hit like a 9-hitter. After beating out Buddy Hassett for the 1B job, Etten had a miserable April. By May 18, he had been demoted to 6th, re-promoted to 5th, and batting a clear .202/.291/.346 while playing 1B. On May 25, seeing Etten’s numbers start to fall, the Yankees promoted Stephen “Bud” Souchock from the minors to play 1st base. The next day, from the farm in Tonawanda, New York (where I live), McCarthy resigned his position as Yankee manager in a telegram.

His ugly season continued as McCarthy’s replacements had Etten pinch hit more than play 1B. Etten’s time in New York continued to dwindle with Souchock getting more playing time. In 108 games, Etten hit .232/.315/.365 with 49 RBI, 9 home runs and only 75 hits (drastic drops from one year ago). On April 14, 1947, the Yankees sent Etten back to the Phillies, but after having a miserable start to the 1947 season, they sent him back to the Yankees. With the Yankees, he played in the minors for the Newark Bears and Oakland Oaks of AAA. In AAA, he hit .256/.369/.439 in 93 games.

He had one AAA resurgence in 1948, playing for the Oaks, where he hit .313/.407/.587 in the hitter-friendly Pacific Coast League. There, Etten hit 43 home runs for the Oaks in 164 games, with 181 hits, 155 RBI and 27 doubles. That was a career minor league season for Etten. He never repeated it. In 1949, he joined the Braves minors, playing in Milwaukee for their AA franchise and hit .280/.408/.454 in 148 games. In 1950, aged 36, he joined the White Sox and their Memphis franchise. There, he hit .313/.487 in the South Atlantic League.

With his career over, Etten retired to his home in Chicago. In 1953, Etten became a player agent for a Beverly-Morgan Park pony league. Home with his kids and his wife Helen Patricia at 10214 Oakley Avenue, Etten eventually became a contractor and part-owner for the Carroll Construction Company in Oak Lawn. He moved to Hinsdale, the community he lived in until his death. His son Nick Jr. became a football star himself in the Cook County area. He was soon inducted into the Chicago Sports and Catholic League Hall of Fames for his time in baseball as well as his success at St. Rita’s.

In 1982, he told the Chicago Tribune about his time with the Yankees and about wearing the iconic #5 while DiMaggio was gone. He noted that he would’ve played third base left-handed if necessary to be on the team. He also told the paper that in 1933 he played for a pickup team at Portage Park in Chicago in which he played three innings with a clown outfit on. He kept the paint on after the game until 63rd Street and Kedzie on his way home.

On October 18, 1990, Etten passed away in his home at Hinsdale at the age of 77. His wife, Helen Patricia along with his daughter Patricia and three sons, Nick Jr, John and Thomas along with one of his elder brothers all survived him. He was buried in the Queen of Heaven Catholic Cemetery in Hillside, Illinois. Helen Patricia Conway Etten died in August 1995 at the age of 79. His elder brother, Joseph Etten, died in 2004 at the age of 97.

Nick Etten’s career is another one, unfortunately, shrouded by the war era. However, much like Snuffy Stirnweiss, these guys were legitimate prospects with legitimate chances. Yes, both of their careers died after the war, but baseball is cruel. Etten will forever be the forgotten American League home run king.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.