We’ve all heard the argument before. If high strikeout pitchers are so great, then why aren’t high strikeout batters so bad? Most will argue that you want a guy at the plate who puts the ball in play when you have men in scoring position, and that’s certainly true, but it’s an oversimplified look at things. Mark Teixeira, the number three hitter for the best offense in baseball last season, had runners in scoring position in just over 31% of his plate appearances. That’s it. Miggy Cabrera, the cleanup man for a middle of the pack offense, had men in scoring position in just over 25% of his plate appearances last year. We can’t just ignore the other chunk of plate appearances because of our confirmation bias, though that’s usually what happens.

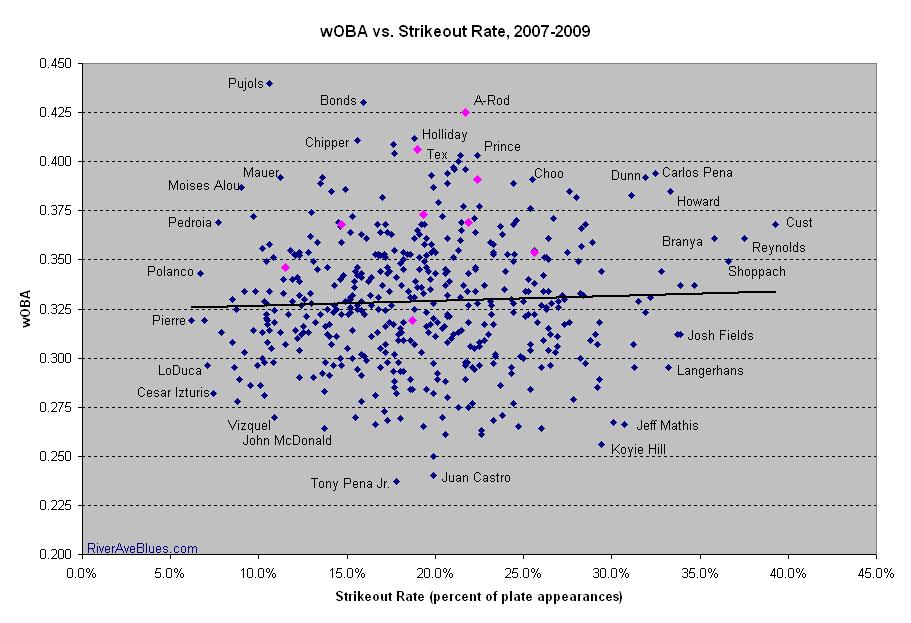

The Yankees struck out fewer times than all but one AL team last year, so we have the best of both worlds. Dis-ir-regardless, I decided to look into this a bit. What I did was take every batter with at least 400 plate appearances over the last three seasons, and plotyed their strikeout rate against their weighted on-base average (wOBA,, which Joe explained in detail here). If strikeouts are so bad for hitters, then theoretically the players with the highest wOBA’s would have the lowest strikeout rates, and vice versa. As always, make sure you click on the graph for a larger view. Oh, and current Yankees are in pink to make life easy.

So how about that. The data seems pretty spread out, no? The two data points between Chipper and Holliday/Tex are Hanley Ramirez and Chase Utley, and the other two .400+ wOBA players (between Holliday/Tex and Prince) are Manny Ramirez and Ryan Braun. I didn’t want to go too crazy with the labels and clutter things. The R² of the trendline is microscopic at 0.0021, which suggests there’s basically zero correlation between strikeout rate and overall offensive production.

Now don’t get me wrong, I’m not trying to say that strikeouts are good. They’re bad, we all know it. However, it’s okay to sacrifice a few strikeouts from position players in exchange for other things, like hitting for power or getting on-base at better than average rates. Just look at the graph, you can see that almost all of the players with really high strikeout rates (say, 33% and above) are generally above average offensive players. If that many of your plate appearances end in strike three, you better do other things well at the plate, otherwise you’re useless. Adam Dunn, Ryan Howard, Carlos Pena, Mark Reynolds … all those guys make up for their strikeouts by hitting baseballs far, far away.

At the same time, look at all the low strikeout players that are offensive black holes. Omar Vizquel, Cesar Izturis, John McDonald … those guys contribute nothing with the bats. If you had men in scoring position, they’re the last people you’d want up because they’re the least likely to do something positive. It doesn’t matter that they don’t strikeout much, their wOBA shows they’re offensively inept. The only reason they’ve managed to keep their jobs is because they’re outstanding glove men. It’s a trade off, just like high strikeout totals.

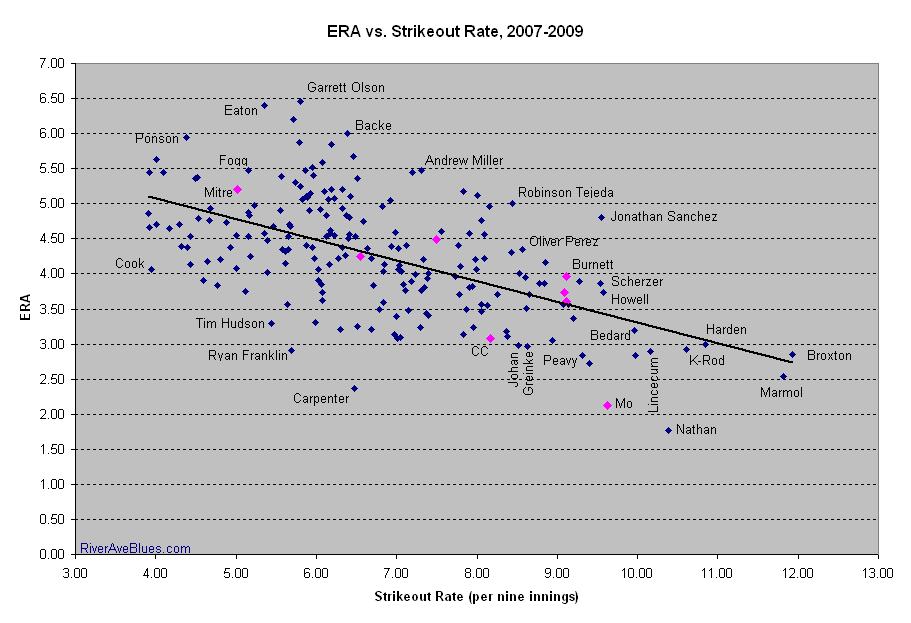

Now what about the other side of the coin? How do strikeout totals affect a pitcher’s performance? For that, I plotted ERA vs. strikeout rate, which I know isn’t perfect. Ideally I’d plot their opponent’s wOBA instead of ERA, but I don’t have that data handy and I’m sure as hell not going to take the time to calculate it. This will have to do for now, but yes, I’m very aware of the flaws. Same deal as above, pink data points are Yankees, click for an enlargisized view.

The two pink data points just below Burnett are Joba and Javy Vazquez, while Andy Pettitte and Chad Gaudin are a little further up the scale.

Unlike wOBA, there’s a pretty significant correlation between strikeout rate and ERA, and it’s easy to see from the graph. The R² of the trendline is 0.33, although we don’t know if that tells us anything meaningful because our sample isn’t very big (I limited it to pitchers with at least 200 IP over the last three years to weed out as many relievers as possible). However, it’s safe to say there’s a (much) bigger correlation between strikeouts and pitching success than there is with offensive success, and it’s pretty obvious in the graph.

The low strikeout guys are higher up on the ERA scale, while the higher strikeout guys are further down. You start at Sidney Ponson and Sergio Mitre then ride the slide down to Zack Greinke and Tim Lincecum. It’s not a coincidence. Strikeout pitchers are the most effective because they take their defense right out of their equation. Like hitters, there’s a trade off, you can live with low strikeout totals if a pitcher does other things well. However, there’s only so much a pitcher can do to make up for it. They can generate an extreme amount of ground balls and limit walks, but even that only goes so far. If you can’t get hitters to swing and miss, you’re going to give up hits. If you give up hits, you’re going to give up runs. It’s just the way it is.

All this post does is reinforce what we already knew: you could still be a good, even great hitter despite striking out a ton, but chances are you won’t be very effective on the mound if you can’t strike out a decent amount of batters. Oh sure, there’s definitely some exceptions, but they’re few and far between. We all hate watching players strikeout when there’s ducks on the pond, but there’s so much more to the game than that.

Photo Credit: Kathy Willens, AP

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.