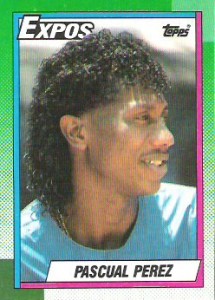

The following is a guest post by my dear friend David Meadvin, with some assistance from me on the statistical/research front. Dave previously contributed to TYA as an occasional guest poster, and is probably the world’s biggest Pascual Perez fan. We’re talking about someone who, as a nine-year-old, literally filled three nine-card binder sheets up with nothing but the same exact 1990 Topps Pascual Perez card seen at the right (that’s twenty-seven (!) identical cards) for reasons that remain unclear to this day.

On a warm Dominican spring morning in 1957, Pascual Gross Perez came into this world – and Major League Baseball would never be the same.

I’m not ashamed to admit that I’m not an advanced stats kind of guy. I’ve never been that interested about baseball on paper; I love the game because it’s unpredictable in a way that stats can never fully capture. When Larry and I were growing up dodging beer bottles at Yankee Stadium and trading Topps cards, I was never a huge fan of the big stars. Sure, I loved Don Mattingly and Darryl Strawberry (I know he was a Met, but good God what a swing) – but my heart was always with the oddballs. And there have been few odder balls in MLB history that Pascual “I-285” Perez.

One of the many strange things about Perez is that his Minor League performance was mediocre at best. Signed by the Pittsburgh Pirates as an amateur free agent out of the Dominican Republic in 1976, Perez spent five years in Pittsburgh’s minor league system putting stats that hardly screamed “I’m ready for The Show.” In 1979, at AAA, he threw 103 innings of 5.50 ERA ball with an ugly 4.5 K/9 and 4.1 BB/9. He improved considerably the following season at AAA, throwing 160 innings of 4.05 ERA ball with a 5.9 K.9 and 2.7 BB/9, and he made his MLB debut on May 7, firing six innings of three-run ball, then getting sent right back down for his troubles. At the age of 24, Perez started the 1981 season at AAA for the third consecutive year. Today, it’s hard to imagine a pitcher with his minor league stat line ever seeing the bigs, but with a staff that was fronted by John Candelaria, a struggling Rick Rhoden, an ancient Luis Tiant and no one else anyone’s ever heard of, the Pirates were clearly desperate for pitching.

As a result, despite a 4.94 ERA and a worse walk rate (4.1 per nine) than strikeout rate (a paltry 3.2), Perez earned a Mid-May call-up. At the Major League-level, Perez actually pitched slightly better than his MiLB number might have indicated, but still, he was hardly a star. He tossed 86.1 innings of 3.96 ERA/3.57 FIP ball — numbers that few would frown upon from a middle-of-the-rotation starter these days, but back in 1981 were 10% and 1% worse than league average, respectively. Not to mention the fact that Perez still wasn’t striking anyone out, with a 4.8 K/9. Unimpressed, the Pirates demoted Perez back to AAA for the start of the 1982 season, which prompted the Dominican to consider leaving Major League Baseball and returning to the Caribbean League. Fortunately for all of us, the Atlanta Braves decided to take a chance on him and acquired him in a trade for Larry McWilliams, who had pitched to a putrid 6.21 ERA/1.91 WHIP the season before, but somehow managed to put up two solid years for the Pirates in 1983 and 1984.

The Braves may not have known exactly what they were getting in the rail-thin Perez, but it didn’t take long to find out. On August 19, 1982, Perez was scheduled to make his debut start in Atlanta. As game time approached, Perez was nowhere to be found. When Perez finally showed up – well after the game began – he explained that he drove around I-285 three times looking for the ballpark before finally running out of gas. Here’s how the story was reported in Sports Illustrated:

“When I get lost, I been in Atlanta for four days,” says Perez. “I rent a car and get my driving permit that morning, and I leave for the stadium very early, but I forget where to make a turn right.”

Thus handicapped, Perez made an afternoon-long ordeal out of what is normally a 15-minute ride. Circling helplessly, he finally pulled off the freeway at about 7:10 p.m., well north of Atlanta and running on fumes, and using gestures and his minimal English, persuaded a gas-station attendant to pump $10 worth of free gas for him. “I forgot my wallet, too,” says Perez.

The incident earned Perez the nickname “I-285,” which he proudly wore on the back of his warmup jacket. As Yankees fans are well aware, the Braves’ manager at the time, Joe Torre, is not known for treating rookies kindly – much less rookies who miss their first start. In fact, a famed poster commemorating the incident is described as including a mural of Torre, looking baffled, staring at his wristwatch. If anyone owns this poster or can unearth even a JPEG of it, please let us know [UPDATE: We finally secured a copy of this poster during the summer of 2012].

Surprisingly, Torre stuck with the enigmatic righthander. Incomprehensibly, Perez’s mishap lit a fire under the Braves. Heading into his Braves debut, the team was mired in a 2-19 slump. Yet, according to Sports Illustrated, the team “found the mishap so hilarious that they laughed their way into a 13-2 winning streak and then went on to win the National League West, thereby making Perez’s ride more familiar to Atlanta schoolchildren than Paul Revere’s.” The title run was also helped by Perez’ 79.1 innings of 82 ERA-/89 FIP ball for the Braves that season despite a K/9 of just 3.3(!).

Perez also began establishing a reputation around Major League Baseball that season for on-field antics that included shooting batters with an imaginary finger-gun, peering through his legs to see what kinds of leads baserunners were taking, regular beanings and threats, an occasional eephus pitch (which would come to be known as the “Pascual Pitch” in certain circles), and of course his gleaming curly locks. As one opposing manager proclaimed, “there’s not enough mustard in the State of Georgia for Mr. Perez.” Perez’s response? “Everybody mad at me because they think I try to hit somebody, but I don’t try to hit nobody. The coaches tell me, ‘Don’t be afraid sometimes to pitch inside,’ so I do it.”

Coming into the 1983 season, the Braves saw Perez as an emerging star, and he lived up to their expectations, posting the best season of his career. He threw 215.1 innings of 3.43 ERA (90 ERA-)/3.39 FIP (87 FIP-) ball, with a 6.0 K/9 and 2.1 BB/9, worth 4.1 fWAR. Sadly, Perez found himself jailed in the Dominican Republic in the offseason on drug charges. After his release, he returned to the Braves in May 1984 and proceeded to win 14 games the remainder of the season. It’s not out of the realm of possibility that if not for his jail time, Perez would have been a 20 game winner in the ’84 season.

In 1985, everything fell apart. Perez served three stints on the disabled list with shoulder pain before earning a team suspension in July for disappearing somewhere between New York and Montreal. After finishing the year with a heinous 1-13 record, Perez, who just a year earlier was seen as an emerging ace and probably would have been unanimously elected mayor of Atlanta, was released by the Braves.

1986 is a complete mystery. There is no record of Perez throwing a single pitch in any organized baseball league, or even what he did with his time.

Fortunately, the Pascual Perez story was not over. Prior to the 1987 season, the Montreal Expos managed to track him down and signed him to a minor league contract. Visa problems kept him from entering the United States until May, but after several months of minor league ball, Perez made his return on August 22, 1987, throwing five innings of three-run ball against the Giants. He finished the year a perfect 7-0. This time, Perez appeared to have finally figured it out with Montreal, enjoying the finest three-year stretch of his career as he threw 456.2 innings of 2.80 ERA (80 ERA-)/3.05 FIP (85 FIP-) ball, upping his K/9 6.7 and walking almost no one, with a 2.1 BB/9. In 1988, he pitched a rain-shortened, five inning no-hitter.

After an uninspired 1989 season, the Yankees came calling. Coming off two straight fifth-place seasons and utterly desperate for starting pitching (their starters pitched to an MLB-worst 121 ERA- from 1988-1989), the Yankees decided to invest 3 years and $5.7 million in Perez.

The big-bucks investment didn’t exactly pay off. Prior to throwing a single pitch for the Yankees he arrived seven days late to spring training with what the Yankees described as yet more “visa problems,” prompting then-Expos manager Buck Rodgers to describe Perez as “a time bomb that the Yankees will have to monitor closely.” In his third start that season, Perez departed with an ailing arm that required rotator-cuff surgery that August. He also could have invested in a datebook or personal assistant, as Pascual showed up 10 days late to spring training in 1991, and five days late in 1992.

The thing is, when Perez actually took the mound he was effective, putting up a 2.87 ERA and 3.60 FIP in 1990 and 1991. But he only pitched a total of 87.2 innings spread out over two seasons. For whatever reason, he just couldn’t stay healthy (or present) for long stretches during his time in pinstripes. It all came crashing down in 1992 — the third and final year of Perez’s big contract – when he was suspended by MLB violating the league’s drug policy. This forced him to forfeit the remaining $1.9 million left on his contract.

Despite these myriad setbacks, the Yankees were actually interested in retaining Perez’s services. The New York Times reported that general manager Gene Michael placed about 60 calls to him over the offseason, but never heard back. Perez, who once referred to himself as “one of five twin brothers,” (one of those five, Melido, of course also pitched for the Yankees, and gave the Bombers quite a bit more than Pascual ever did, posting a 4.06 ERA/3.84 FIP over 631.1 innings from 1992-1995) had fallen deep into the Dominican Republic, far from the grasp of Major League Baseball.

Despite the Yankees’ best efforts, to this day, Pascual Perez has never been found. He may be gone, but his legacy lives on in the hearts of fans everywhere who consider him a hall-of-famer in baseball’s theater of the absurd.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.