The following is a guest post from Adam Moss, who you know as Roadgeek Adam in the comments. He’s previously written guest posts on Tim McClelland, Frankie Crosetti, the No. 26, Casey Stengel, Leo Durocher, Miller Huggins, Jerry Kenney, the Copacabana incident, and Mark Koenig.

It seemed to be just another day of baseball at Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis, Missouri on Tuesday, July 24, 1934. Johnny Murphy was throwing for the Yankees a game of one-run baseball. The Yankees held a small 2-1 lead over the Browns. The players were pretty much drained by the seventh inning because of the 109 degree ambient temperature in St. Louis, which felt more like 120+ in the ballpark. During the seventh inning, Murphy gave up a long fly to the Browns’ Harland Clift, and the left fielder ran after it at full speed. Before he knew it, he crashed into the left field wall, made completely of concrete. The force of the impact was so powerful that the player rebounded off the concrete and fell on the ground, lying completely still. After rushing to his aid, players carried the injured outfielder to the clubhouse with bruises and bleeding, very much dazed. Before the end of the game the precious career and the life of a player for the Yankees was in the hands of a hospital in St. Louis.

The Kentucky Kid

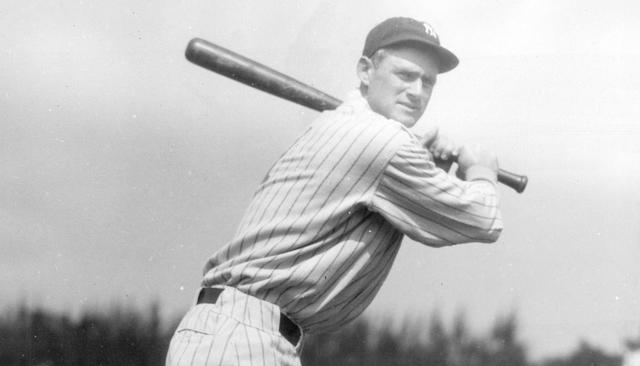

Earle Bryan Combs was born on May 14, 1899 on a farm in a small community 56 miles southeast of Lexington, Kentucky called Pebworth. Combs was one of six children by farmer James J. Combs (born 1860) and Nannie Brandenburg (born 1869). As a kid, young Earle would make baseballs for his local team to use as a baseball player. In addition to his work playing baseball as a kid, Combs also played for the local basketball team in Owsley County. Combs was accepted to Eastern Kentucky State Normal School in 1914 and received a certificate in teaching in 1919. His first love was always baseball, and when playing for the Eastern Kentucky Colonels, scouts caught attention of the 6-foot, 170 lb. 22-year-old who was playing the outfield. In 1921 with the college team, Combs had managed a batting average of .591!

Combs began to teach at a one-room school at Harlan, Kentucky until realizing that he could probably make more money as a baseball player than a teacher. In 1922, he signed with the Louisville Colonels of the American Association and played for manager Joe McCarthy. In his very first game as a Colonel, Combs made several errors in the outfield, which led to their opponents winning the game. The young Combs after the game was concerned about his ability to play and that he would wonder what would happen to him and his wife Ruth. McCarthy quickly eliminated any doubt about his potential, knowing he had a great player. Combs responded to McCarthy’s support, hitting .344 and slugging .487. In 130 games, he managed to get 167 hits, 21 doubles, 18 triples and slug four home runs.

1923 was a much better season under McCarthy’s leadership, when in 166 games, the 24-year-old Combs hit at an astounding .380 average and a .566 slugging. His overall peripherals also improved, with 241 hits, 46 doubles and 14 home runs. (His triple rate went down to 15, but that’s bookkeeping.) On January 7, 1924, the Louisville Colonels announced that Wayland Dean, a pitcher, was sold to the New York Giants for $50,000 (1924 USD). Also reported by the Colonels was that Earle Combs was sold to the New York Yankees for the similar amount, along with outfielder Elmer Smith. At the time, the $100,000 acceptance for their players was the record for the American Association. The so-called “Mail Carrier” had made the Majors.

From the Mail Carrier to the Waiter

Now as a member of the Yankees, Miller Huggins decided to have a long talk with the young Combs about his purpose on the team. Huggins changed his title from “Mail Carrier” to “The Waiter,” noting that rather than use his base stealing abilities, just wear out a pitcher and get on base, that way people like Ruth can just knock him in for a run. Combs took Huggins’ advice, and the numbers ended up reflecting themselves in 1924. During the 1924 season, Combs stole no bases and was caught stealing once. However, his statistics that season reflect all of 24 games, because on June 15 during a game against the Cleveland Indians, Combs broke his right ankle in front of 30,000 people sliding into home plate. Harvey Hendrick replaced him in left field. While multiple reports note that Combs was out for the season in 1924 after the ankle fracture, he managed to squeeze one more game in during the 1924 season: September 2’s first game against the Boston Red Sox. Combs was able to pinch hit in his only appearance for Al Mamaux. The loss of Combs is considered a reason the Yankees lost the pennant in 1924 to the Washington Senators by two games.

Returning to the Yankees in 1925 as a fully-healed player, Combs went to work being The Waiter. By the end of the April, Combs had been hitting .378/.439/.459, spending most of May above a .400 batting average (peaking on May 6 at .467/.543/.583). Combs did not fall under the .400 line until after the game on May 27, 1925 against the Boston Red Sox. As the dog days of summer passed, Combs’s line below .350 on August 6 against the Detroit Tigers, but would not fall much further. The lowest Combs would ever reach is .336 on two occasions: August 29 against the Browns and September 2 against the Red Sox. Combs finished the season with an absurd batting line: .342/.412/.462. On top of that, Combs eked out 203 hits, 36 doubles and 13 triples along with three homers. The Waiter also managed 65 walks over 43 strikeouts. For the SABRmetrics geeks, he represented 4.0 WAR for the 1925 Yankees, receiving an MVP vote and finishing 18th.

1926 represented a very blip-ish season for the Yankees outfielder. Hitting a paltry .299, Combs never broke the .350 barrier after April 21 against the Red Sox. Despite the questionable season for Combs, which involved getting 181 base hits (31 doubles, 12 triples and 8 homers), his ability to reach base more than strikeout continued, with his 47 walks over 23 strikeouts. Yes, 23 strikeouts in 145 games. The team still managed to reach the pennant, unfortunately losing to the St. Louis Cardinals in seven games. During that World Series, Combs played in all seven games, hitting .357/.455/.429 with 10 hits in 28 at bats, along with 5 walks.

That brings us to the magical 1927 season. Whatever afflicted Combs during the 1926 season wore off, because the season he had was similar to 1925. Although he spent most of the season batting around the .320 range, Combs managed to hit at a then career-high (base 130 games) .356/.414/.511. Combs set major league highs in plate appearances (725), at bats (648), hits (231) and triples (23) in 152 games. The 231 hits were a record, and it was not eclipsed until Don Mattingly did the job in 1986 with 238. He also hit 36 doubles and 6 homers, along with stealing 15 bases (caught 6 times). He also walked at twice the rate of his strikeouts (62/31) during the 1927 season. During the 1927 World Series against the Pittsburgh Pirates, Combs managed to hit .313/.389/.313 with 5 hits in 16 at bats. While definitely a downgrade from his line in the 1926 Fall Classic, Combs finally got his first ring a member of the New York Yankees, as the Yankees swept the Bucs in 4 games.

Because parity, Combs’s 1928 season reflected his 1926 performance, with Combs managing only a .310/.387/.463 batting line that year. However, it was not for naught. Combs still managed 194 hits, 33 two-baggers and yet another major league high 21 triples. The Yankees still went on to face the St. Louis Cardinals in the World Series, but Combs would be a non-factor. Combs had one plate appearance on October 8 as a pinch-hitter for Benny Bengough. This was due to an injured wrist, which he was claimed to be unavailable for the entire season. Strangely enough, Combs managed to finish sixth in the MVP standings. (Teammate Tony Lazzeri finished in a tie for third!)

For those who would yell “Decline!” after the 1928 season performance were quickly debunked in the 1929 season. Combs started the 1929 season extremely slow, not reaching the .300 batting average line until May 11 against the Detroit Tigers. However, unlike the dog days of summer before, Combs only got better as the season went on, reaching the .350 batting average on June 16 against the Tigers. In the fight to keep up with the Philadelphia Athletics, Combs managed to hit .350 on a regular basis, finishing the season just below that at .345/.414/.468. He also broke the 200-hit barrier for the third time in his career, ratcheting another 202. However, these statistics were overshadowed by the unexpected death of the manager Miller Huggins on September 25. Huggins had loved Combs and Gehrig on his team, and the death of the Mighty Atom affected the newly-nicknamed Kentucky Colonel. The nickname came from the fact that he was a determined person in the field, but also the gentleman of the Yankees. Combs did not smoke or swore like his teammates, focusing on his studying of the Holy Bible.

From Waiter to Non-Factor

1930 would be considered the last excellent season for The Waiter. His statistics under Bob Shawkey’s leadership echoed his 1929 ones. The 31-year-old Combs hit .344/.424/.523 for a third-place team, racking up another 183 hits to his career, including 30 doubles and his third major league high 22 triples in 137 games. That season was the last that Combs would lead any category whatsoever, but he was far from done. In 1931, Combs got a boost from the Yankees hiring his manager from Louisville, Joe McCarthy, and in 138 games, Combs racked up another 179 hits. However, decline finally showed in the 32-year old outfielder. Combs only hit .318/.394/.446. While this is nothing to consider pathetic, by the standard Combs had set before, this was definitely out of whack. He still kept within average on doubles and triples, hitting 31 and 13 respectively and was still the machine when it came to walking versus striking out (another doubled performance: 68 over 34.)

1932 reflected the last great season Combs would have as a Major League player. Combs gained another 190 hits to his resume, running his average back up to .321/.405/.455 overall. The Kentucky Colonel helped lead the Yankees to another pennant in 1932, facing the Chicago Cubs in the World Series. However, unlike 1928, Combs returned to being a factor in 1932 during the Fall Classic. Combs had 16 at bats in the 4 games, racking up 6 hits and 4 walks, batting .375/.500/.625. However, the 1932 World Series was famous more for Babe Ruth’s called homer during Game 3, noting that he could not remember if Babe was pointing to the stands, but that the Cubs were “machine-gunned” when Ruth did exactly what he predicted.

1933 was the clincher for those who call decline, and it showed in his stats. Combs only appeared in 122 games, the lowest since his injury-ridden 1924 season. He only chalked up 125 hits, 22 doubles and somehow managed to leg out 16 triples and five homers. He only hit .300/.372/.465 as the Yankees lost to the Senators for the AL pennant by 7 games. If not for an 8-14 record against the Senators, the Yankees may have gone to the World Series. For the first half of the 1934 season, Combs managed to hit a paltry .319/.412/.434, with 80 hits in 63 games along with 13 doubles and 5 triples. However, all the work he put into season came to a head on July 24 at Sportsman’s Park.

The Accident

During the game against the St. Louis Browns on July 24, Combs was playing in left field. In three at-bats, Combs had failed to reach base, getting only his ninth strikeout of the season. Everyone in the park was pretty drained due to the rough St. Louis heat, 109 degrees ambient and projections over 120 degrees in the ballpark itself. Harland Clift, the third baseman for the Browns hit a long fly off Johnny Murphy that Combs chased into the 370-foot left field of the park. Combs, despite the heat, ran full-speed to catch the ball, and while focusing on the ball, neglected to notice the concrete wall at the edge of the ballpark. Combs slammed head-on into the wall, so powerfully that he rebounded off the wall and fell down.

Combs just lay still while Clift rounded the bases for his third hit of the day. The players panicked seeing the Colonel on the ground and carried him off the field and into the clubhouse, bruised, dazed and bleeding as Myril Hoag replaced him in left. That night he was brought to St. Johns Hospital in the Westwood section of St. Louis County. Dr. Robert Hyland of the hospital examined the injured Combs, who had no idea what hit him, noted that the outfielder had a fracture of the left temporal bone and a fractured left clavicle. While spending most of his time in the hospital in critical condition, Combs managed to have a restful night of July 24 and that he was in satisfactory shape.

The baseball media thought that the injury at Sportsman’s Park would mean the end of the career of Combs, due to the severity. However, Combs was determined to return, citing his time during the 1924 season of breaking his ankle as his reasoning. During the time that he had injured his ankle, the media “counted him out” and that he would never play baseball again. However, he noted that he could fool the media once and believed he could do it again. However, in August as his shoulder completely repaired itself, Dr. Hyland did not want to make suggestions on the effect the injury would have to his career. Combs noted though that as soon as he could leave St. John’s, he would return to his farm in Richmond, Kentucky to prepare and condition himself for the 1935 season.

On September 8, 1934, the time finally came. Combs left St. John’s Hospital to go see the Washington Senators take on the Browns. That game was the first time that Combs had left the hospital since the night of the accident, but Combs would have to return before being discharged the next day. Afterwards, he went to visit his Yankee teammates then headed home to Kentucky. The comeback would be completed on April 16, 1935 when he was put in the Opening Day lineup by manager Joe McCarthy, batting leadoff as the left fielder behind Lefty Gomez. While Combs had a 0-4 day, the fact that he was playing in another game after a life-threatening accident just nine months earlier was a major step forward. Always a fan favorite, Combs was applauded in his return.

Combs noted in the media during an early May series against the Indians that he had told Lou Gehrig that they were getting too old to go all-out crashing into walls, but that when Clift hit the fly ball, he forgot all about it. He noted that it would take another crash into a wall to keep him out of the lineup, and that he would never make the same mistake twice. During the 1935 season, Combs played in 89 games, racking up 84 more hits and still had his excellent eye, getting 36 walks over 10 strikeouts. However, problems reared their ugly heads on August 25 during a game against the Chicago White Sox at Comiskey Park. Chasing another fly ball, Combs and shortstop Red Rolfe collided with Rolfe falling backwards on top of Combs. Combs was spiked and bruised above the right knee, but most painfully, separated his right collarbone from the shoulder blade and ligaments were pulled.

This time, Combs noted that this was probably the end. Noting that he was jinxed, Combs had his shoulder repaired in Manhattan, he felt that the end was near anyway and that he better get out of the way before it got any worse. An issue that would come up is that Combs’s defense would be affected. Combs was never the best outfielder with his arm and such an injury would just inhibit him more. Combs basically decided it would be time to hang up the spikes and head back to Kentucky. Despite the injuries, Combs managed to get into games on September 11 and September 12 against the Indians and Tigers. Combs would sit out until September 25, when McCarthy had him pinch run for Bill Dickey for one last hurrah. After all was said and done, Combs had managed 1,866 hits in 1,455 games, batting an amazing .325/.397/.462 with 670 walks over 278 strikeouts.

Conclusion

For the 1936 season, Earle Combs ended up not going back to his farm, but becoming a coach under McCarthy. During that season, he had to teach a new outfielder about having to play center field at Yankee Stadium. This new outfielder had just come from the San Francisco Seals and was given No. 9 for his first season, Giuseppe Paolo DiMaggio, better known as Joe DiMaggio. Combs would remain coach of the Yankees through the end of the 1944 season, gaining 6 more rings under his time there. In 1947, he joined the St. Louis Browns as a coach under Muddy Ruel. In 1948, he became the first base coach for the Boston Red Sox, a position he held until the end of 1952. On March 30, 1953, 53-year old Combs announced that he quit to spend more time with his family, farm and business interests in Richmond, Kentucky, replaced by Del Baker. However, he chose to spend one more season in the league, being a coach for the Philadelphia Phillies in 1954 under Steve O’Neill and Terry Moore. One of the other coaches on the 1954 Phillies was Benny Bengough, the catcher that Combs had pinch hit for despite being injured during the 1928 World Series.

After the final swan song, Combs made headlines in May 1958 when former baseball commissioner Albert Benjamin (Happy) Chandler talked to Combs about becoming the Kentucky State Banking Commissioner. Chandler became Governor in 1955. The position had become vacant when S. Albert Phillips had left. Combs was a member of the Board of Directors for the Kentucky State Bank and Trust Company in Richmond, and after talking to Chandler, took the job. Combs retained the job until 1960 when H.A. Rogers took the job under new governor Bert Combs. In 1970, the 70-year old Combs was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown by the Veterans Committee along with Lou Bouderau, Jesse Haines and Ford C. Frick. Combs spoke of his teammates Ruth and Gehrig and noted that it was a great honor and that he would never bring shame to the honor.

On July 21, 1976, Earle Bryan Combs, the “Kentucky Colonel” died of a long illness. He was survived by his wife Ruth, and their sons, Earle, Jr., Charles and Don (the Athletic Director and swimming coach at Eastern Kentucky.) His funeral services were held at 2 PM on July 23 at the First Christian Church on Main Street and Richmond. He was then interred at the Richmond Cemetery. His wife would join him in 1989 and his son Earle, Jr. would in 1990.

Earle Combs was probably the greatest leadoff hitter in Yankee history. His numbers from 1925-1933 were historic, and somehow, he is not in with the Yankees legends at Monument Park, with his managers, Miller Huggins and Joe McCarthy along with teammates Gehrig and Ruth. I know a lot of people, especially on this site, would love to see the No. 1 un-retired because of who it was given to, but I think it should’ve stayed retired and kept in the honor of the original and true No. 1, Earle Combs.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.