The following is a guest post from Adam Moss, who you know as Roadgeek Adam in the comments. He’s previously written guest posts on Tim McClelland, Frankie Crosetti, the No. 26, Casey Stengel, Leo Durocher, Miller Huggins, Jerry Kenney, the Copacabana incident, Mark Koenig, and Earle Combs.

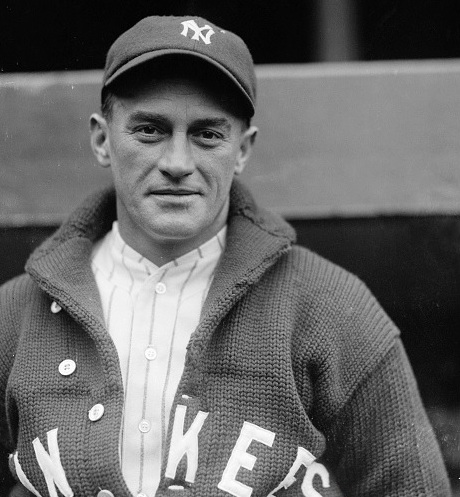

It must have been a dream came true on October 8, 1927 for a 5-foot-10, 170 lb. right-handed pitcher from Cleveland, Ohio named Urban Shocker. In front of 57,909 people at Yankee Stadium, the team that history would consider the most dominant ever, won the World Series on a Game 4 walk-off wild pitch by Johnny Miljus. Urban never threw a pitch in that 1927 World Series despite having won 18 games in 200 innings for the World Champion Yankees. The 1927 season had started out in drama for the Yankees front office and the right-hander, yet, he still provided Miller Huggins what was expected. The man who had been a Yankee long before the rest of the champions was at a crossroads in his 12 year career. The 1928 season would be the last anyone would see from the lanky pitcher.

The Shockcor of Cleveland

The fifth child of a machinist, Urbain Jacques Shockcor came into the world on September 22, 1890 in the city of Cleveland, Ohio. His father, William H. Shockcor (born 1852), worked as the foreman of the Ship Owners’ Dry Dock Company on Old River Street, which did dry docking and general repair work on ships in the Cleveland area. The company had been created by Irishman Andrew Miller, and after Miller died in 1881, his sons ran the company. In 1900, the company was sold to the newly-formed Ship Owners’ Dry Dock Company.

The reason I am covering the history of this company is because in 1907, it was sold to the Chicago Ship Building Company, which sold it to the American Ship Building Company’s Chicago subsidiary. If the name American Ship Building sounds familiar to the Yankee fans, it should. George M. Steinbrenner III’s company (Kinsman Marine Transit) was bought out by American Ship Building in the early 1960s, and as a result, Steinbrenner got a controlling interest in the company, a decade before buying the Yankees.

Enough corporate history for one post; Shockcor’s mother, Anne Katherine (nee Spies) was born in 1858 and made her living as a local dressmaker. Their newborn son in September 1890 was their third son of five children. (The Shockcors would eventually have eight children in total, including another son, Clarence A.J., in 1892.) The Shockcors would soon move to Detroit, with their father becoming a member of the Woodmen of the World, an Omaha-based fraternity of woodmen.

The time in Michigan would be the place where young Urbain would make baseball his life. In 1912, at age 21, the young Shockcor would make his professional debut for the Windsor club of the Level D Border League, which had teams at Wyandotte, Pontiac (nicknamed the Indians), Ypsilanti, Mount Clemens (Bathers), and Port Huron in Michigan, along with the lone Ontario team. During his time at the Class-D Ontario team, Shockcor went between the positions of pitching and catching in 1913. In what historical record we have, he appeared in at least 27 games for the Windsor club, hitting a paltry .149 (.264 slugging). This included 13 hits: 3 doubles, 2 triples and a single home run.

His time as a catcher would be short lived, however, due to a freak accident during the 1913 season. When catching, he stopped a ball with his middle finger on his pitching hand and though the injury healed, it caused a hook at the end of the last joint. Though it ended his catching career, Shockcor found out that the pitching in his right hand was much improved with the injury. The hooked finger gave him a stronger grip on the ball and caused a ball to act like a spitball. In 16 games, the young Shockcor threw 131 innings, allowing 114 hits and 66 runs. His 1.122 WHIP and 2.75 led the team to a 6-7 record with him pitching.

In 1914, the 23-year old Shockcor went to the Class B Canadian League’s Ottawa Senators. This league, mostly within the province of Ontario, had 8 teams (Brantford Red Sox, Erie Yankees, Hamilton Hams, London Tecumsehs, Peterborough Petes, St. Thomas Saints and Toronto Beavers). Playing under player/manger Shag Shaughnessy, the young Shockcor hit in 55 games, with a .223 batting average (22 singles, 1 double) and threw a 2.17 ERA in 236.2 innings, with a 20-8 record.

In 1915, the young pitcher netted 38 singles, with 4 doubles and 3 triples (hitting .277/.350 in 137 AB). As a pitcher, he threw a minor league career high 303.0 innings, pitching to a 1.99 ERA and a 19-10 win-loss record. He struck out 185 players and walked only 40, which he thanked to his slow ball (spitball really) as the Senators won the Canadian League championship in 1915. (They also won the championship in 1912, 1913 and 1914.)

$750 and a Dream

In September 1915, the Yankees selected Shockcor (it’s unclear when he changed his name from Shockcor to Shocker) from the Guleph, Ontario team for $750. The Yankees wasted no time bringing him to Spring Training in 1916. He had a rough start to his Yankee career, because on an intrasquad game of March 16, 1916, he was spiked by Tim Hendryx on a grounder down the first base line. The stubborn Shocker was supposed to be out several weeks, but he managed to return on March 21.

Shocker made two appearances in the early parts of the 1916 season, once against the Washington Senators at Griffith Stadium, throwing three innings of two-run ball in relief of Bob Shawkey and Nick Cullop. The second was on May 3 against the Philadelphia Athletics at Shibe Park. This time, Shocker gave up 2 runs in 1 inning in relief of Ray Keating. The Yankees put him on waivers and sent him to the Toronto Maple Leafs of the International League on May 15. Bill Donovan and the front office had to choose between Shocker and Dan Tipple. Where Shocker only cost the Yankees $750, Tipple had cost the team $9,000! The fight to keep Shocker could be considered bloody, as the Yankees had $1,500 offers for him to play elsewhere.

The decision to send Shocker to Toronto paid off. Shocker went to Toronto and became an immediate ace. In 24 games (20 starts), he won 15 and only lost 3. The .833 winning percentage led the International League, but his 1.31 ERA did not. He only gave up 115 hits and 27 earned runs along with 73 walks and 152 strikeouts. This amazing season in the IL included an 11 and a 13-inning no-hitter for the 25 year old Shocker. Shocker threw 58 straight scoreless innings in Toronto at one point in time, and there was predictions by then that Shocker would be back in a Yankee uniform before the season of the IL was over. This was indeed the case.

On August 12 at the Polo Grounds, Shocker turned an 8-inning performance of 2 hits, 1 run, 1 walk and 7 strikeouts. He would be replaced in the 9th by Shawkey, but lost because Bullet Joe Bush threw a shutout and second baseman Joe Gedeon made a costly error. Shocker’s pitches were reported by The New York Times as “darting around like a Mexican jumping bean.” At the end of the season, Shocker accounted for 12 games, including 9 starts. Of those 9 starts, 4 were complete games, and 1 was a shutout. His W-L record finished at 4-3 and he only gave up 2 home runs in 82 IP. He struck out 43 batters, and walked only 32. Offensively, Shocker had 21 at bats, recording 4 hits, 1 RBI, 5 walks and 2 runs scored. His official batting line was .190/.370/.190. Shocker made $1,350 total.

In 1917, the young Shocker found himself permanently etched into the Yankees rotation under Bill Donovan. The 1917 season, however, ended up being a trying year for the young spitballer. Shocker tended to drink and when he was in Boston during the season, he and spitballer Ray Caldwell (who was known to be a heavy drinker) were fined by Donovan for not returning to the Lenox Hotel (an upscale hotel in the Back Bay) by midnight the night after a game. Shocker received a first-offense lenient penalty of $50 ($927 in 2016) while Caldwell was slammed for his drinking. Caldwell was fined $100 ($1,855) on June 29 for his actions, as well as suspended without pay for the next ten days. Both Shocker and Caldwell had managed to violate training rules and the latter did not show up to Fenway Park for the next game. (Caldwell would be fined by Ban Johnson in August for intentionally getting himself ejected by umpire Silk O’Loughlin because he didn’t want to have to perform in the game or be with his team.)

Statistically, 1917 was also trying in terms of the performance on the baseball field for the 26-year old. Shocker appeared in 26 games for the Yankees, but only started 13 of them. In those 13 games, Shocker had 7 complete games (no shutouts) and accounted for a 104 ERA+ (a drop from his 112 ERA+ the previous season in a smaller sample size.) In all, Shocker matched his 1916 season in ERA (2.61) and managed to only give up 5 home runs, while sustaining a 68/46 strikeout/walk rate.

While there was improvement over the 1916 team, Donovan and the front office traded Shocker in January 1918, along with catcher Les Nunamaker, utility man Fritz Maisel, pitcher Nick Cullop, super-utility man Joe Gedeon, and $15,000 to the St. Louis Browns for pitcher Eddie Plank and utility man Del Pratt. Plank would end up refusing to report to the Yankees and retired. This trade has been considered one of the most lopsided deals the Yankees have ever made. Miller Huggins, now in charge of the Yankees, was told that Shocker had a poor personality, and in 1925, noted that he never would’ve traded him had he known more.

To The Browns and Back

Because this is a Yankee blog, I’m not going to spend a lot of time talking about Shocker’s time in a Browns uniform. However, I will note a couple important things about his time in the St. Louis uniform. The first is that Shocker’s trade would be made even worse because he became an ace against his former team. The New York Times called him “The Great Nemesis” of the Yankees.

Second, his 1918 season was interrupted by World War I and his requirement to go to serve after being drafted. On June 31, 1918, Shocker reported to duty, but that didn’t stop him from pitching. He pitched for the Battle Creek, MI based baseball team. Shocker had given the Browns 9 starts and 5 relief appearances before ending the season abruptly.

The 1919 season was also interrupted by his military service (this time at the beginning; he returned from war on April 1). Shocker threw an average season for the Browns, who had him make 25 starts and 5 relief appearances. His stats would amount to a 2.69 ERA and a 13-11 record. At the end of the 1919 season, the spitball was banned by baseball’s managers. After lifelong Cleveland Nap/Indian Ray Chapman was killed by the Yankees’ Carl Mays on August 17, 1920, the league banned it following the 1920 season. The 17 spitballers in the league, including Caldwell and Shocker, were allowed to continue to throw it under a grandfather clause.

After the 1920 season, Shocker became the ace of the Browns and went on a rampage. In 1921 and 1922, the young Shocker started 38 games for the Browns and threw over 300 innings both times. His ERA during those times fluctuated, with a 2.97 ERA in 1922 and 3.41 in 1922. Three of his known ejections also occurred in the Browns uniform, for bench jockeying in 1920 and arguing balls and strikes twice in 1922 and 1923 respectively. On December 17, 1924, the St. Louis Browns traded Shocker back to the New York Yankees for the aforementioned Bullet Joe Bush, pitcher Milt Gaston (who would live to 100 (died in 1996)) and pitcher Joe Giard (Giard would end up being a Yankee again in 1927).

The Second Time Around

In 1925, now suited for his best chance at a championship ring, Shocker returned to his old team, now under the leadership of Babe Ruth. Miller Huggins noted his regret for the trade on the day of the announcement, saying it was a “grave injustice” that he was ever traded Shocker in the first place. The spitballer had a pretty average season for the Yankees, with a 3.65 ERA in 30 starts (41 appearances in total) and came to a 12-12 record for a seventh-place Yankee teams. In 1925, he also maintained an 88/52 strikeout/balls rate, giving Miller Huggins a 117 ERA+ performance. However, during the 1925 season, the health problems began to show, without anyone’s knowledge. Shocker developed a heart ailment, but he kept the details to himself.

The 1926 season was the year Shocker had waited so long for. The 1926 Yankees were a healthy team, and Shocker led a young rotation to the American League pennant with a 3.38 ERA in 32 starts (9 relief appearances). His record was 19-11 and represented a 114 ERA+ on the Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig-led Yankees. That year the spitballer finished third in wins (19) and winning percentage (.633), along with a fifth-place showing in lowest opponent OBP.

The pennant-winning team sent Shocker to start Game 2 of the 1926 World Series against the great Grover Cleveland Alexander and the ace nearly matched Alexander. Urban mixed his pitches (spitters, curves, off-speed and fastballs) except for a Billy Southworth homer that gave the St. Louis Cardinals the lead for good. Shocker still wanted to start once again, leaving Huggins with the decision of pitching Bob Shawkey or Shocker in Game 6. Huggins chose to start Shawkey and kept Shocker ready for a Game 7. However, Shocker ended up being used in a 5-1 game from the bullpen and gave up a homer and single before retiring the side. The Cardinals won the game 10-2 and Shocker was furious that he had to come out of the bullpen in Game 6 and not start the game.

The 1927 season was the year everything came together for the great Shocker. Shocker led a pitching staff that included Waite Hoyt, George Pipgras, Wilcy Moore, Herb Pennock and Dutch Ruether. The team ran away with the pennant while Shocker threw 200 innings in 27 starts, pitching to a 2.84 ERA and an 18-6 record (.750 winning percentage (second highest in the majors that year). For the second consecutive season, Shocker walked more players than he struck out, despite the improved numbers everywhere else.

Shocker turned in his Yankee-best 137 ERA+ (his career high was 150 in 1918) and Babe Ruth had high respect of the spitballer. Ruth noted that “Rubber Belly” had gotten older, but was smart enough to make sure he could control the ball any way he wanted. Shocker’s health was deteriorating quickly from the heart ailment and when the 1927 World Series approached against the Pittsburgh Pirates, newspapers notes Shocker was the best pitcher the Yankees had, and that the Pirates were terrible against him.

The sweep of the Pirates meant Reuther and Shocker were not called for their starts. Shocker apparently had acquired heart disease circa 1925 and only a few knew of it. When December 1927 came around, Shocker’s health had continued to collapse. Shocker, who had weighed in at 170 for most of his career, had dropped to 115 and was fighting for his life. Shocker decided the time was right to pack it in, especially after sending the Yankees a message of his displeasure with them by sending his 1928 contract back unsigned. Shocker announced his retirement on February 16, 1928 (after a media brew-ha-ha in which Miller Huggins stated that they were ready to move on) stating that he wanted to devote time to his radio work in St. Louis and that his career was over with a good record.

The End

By April, though, Shocker had second thoughts and applied to be reinstated. Kenesaw Mountain Landis approved his application, letting him return on April 7, 1928. Seventeen days later, the Yankees signed Shocker to a 1 year/$15,000 deal and he would prepare to pitch. The press kept his wishes, making no comment about his health. On May 30, Shocker made his only appearance of the season, replacing Al Shealy in relief of a 3-0 games against the Washington Senators. He gave up three hits in two innings, but did not give up a run.

Throwing batting practice a few weeks later at Comiskey Park, the dying Shocker collapsed on the field. On July 7, 1928, after passing through waivers, Shocker was released from the contract he signed. Shocker noted that he took the deal in April because Yankees owed him $1,500 for moving expenses in 1925 for the trade back to the Yankees and the front office refused to pay it. Even after Huggins offered to pay the money himself, Shocker refused, only accepting the money from the club. He noted that he got his money back, four years late.

As for the post-release time, Shocker went to Denver to get his career revived, as well as seek medical attention for his heart disease. Despite playing for an independent team in Denver, Shocker was admitted to St. Luke’s Hospital in Denver (the City Park West neighborhood) on August 13 for pneumonia. His wife spent his time at his bedside, listening to the Yankees win the pennant in 1928. Playing in a tournament in Denver on August 6, he was also stricken with what doctors called athlete’s heart (AHS), which is when the human heart grows and the resting rate is slower than normal. It is common in those who exercise over an hour a day, especially those who do endurance training.

On August 15 it was reported that Shocker was supposedly improving, but his wife Irene noted that he had a broken heart because he missed being in the pennant race with the Yankees. Shocker loved the game to the day he passed, listening to them 1,500 miles away in his death bed. With each loss, he felt the pain of the team losing, and with each win, he felt the joy in their victory.

Urbain Jacques Shockcor died at 7:10 am on September 9, 1928 at the age of 38, with the mix of pneumonia and heart disease. While the doctors used the medical reasons for his death, his wife cited the broken heart for the team. Even by the Friday before his death, they felt he had a chance to recover, but he had a relapse, leading to his death. On September 12, the Yankees announced that they would attend Shocker’s funeral, if it was delayed so they had the free chance before a series against the Browns.

Shocker’s body was moved from Denver to St. Louis, where over 1,000 mourners attended his funeral ceremony at All Saints Catholic Church. Lou Gehrig, Herb Pennock, Earle Combs, Mike Gazella, Gene Robertson and Waite Hoyt all served as pallbearers at his funeral. Brother Benjamin, the pastor at St. Mary’s Bays School in Baltimore (which Babe Ruth attended) also attended the funeral. The casket was brought to Calvary Cemetery in the northern end of St. Louis, where he was buried. The mood of the funeral carried over into the Yankees series against the Browns, who kicked them around.

Shocker’s career ended with a .615 winning percentage (187-117) in 412 games (317 starts) with a 3.17 ERA. This included 200 complete games and 28 shutouts. Though the save statistic would not be created until 1959 by Jerome Holtzman, Baseball-Reference credits him with 25 saves. Pitching to career 124 ERA+, Shocker faced 11,137 batters, striking out 983.

Shocker was one of the greatest spitballers in Yankee history, and if the ill-fated trade of January 1918 had never occurred, I’m confident there would be a plaque in Monument Park for the man who was really the first ace of the Miller Huggins era. It would only be fair. The kid from Cleveland became one of the best baseball pitchers in the American League and was gifted with an 80 name tool. The story of his early demise only leaves speculation to what Shocker could have been in 1928 and onward, but speculation is not for this historian.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.