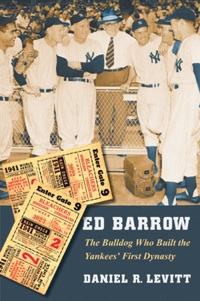

The following guest post comes to us from baseball historian Daniel R. Levitt. He is the author of Ed Barrow: The Bulldog Who Built the Yankees’ First Dynasty, a book I reviewed in 2008 which is now available in paperback

The following guest post comes to us from baseball historian Daniel R. Levitt. He is the author of Ed Barrow: The Bulldog Who Built the Yankees’ First Dynasty, a book I reviewed in 2008 which is now available in paperback. It was one of three finalists for the 2009 Seymour Medal, an award honoring the best book of baseball history or biography published during the preceding year.

Baseball, like all businesses, responds and adapts to its economic environment. The greater the disruption, the more profound the adjustment. The economic disorder of the Great Depression shocked the baseball owners: total profits of major league baseball collapsed from $1,335,742 in 1929 to a loss of $1,651,530 in 1933. Some of the less well capitalized owners were forced to sell their best players to raise capital. This expedient reached its apex in 1934 when Washington sold future Hall of Fame shortstop Joe Cronin to the Red Sox for $250,000, an amount greater than the entire 1933 player payroll of 14 of the 16 teams.

But the most lasting effect of the Great Depression on baseball was the realignment of the major and minor leagues. Like today, teams were limited to a 25-man roster of players during most of the season and a 40-man roster overall. The 15 players not on the 25-man roster were typically on option to minor league teams for continued development. Today, of course, teams control many, many more than 40 players though their farm systems. Prior to the Depression, however, this was not generally possible; all players on minor league teams controlled by a major league club counted against the 40-man roster. Some of the smoother operators, such as St. Louis’s Branch Rickey managed to skirt the edge of these rules, but on the whole having a farm system offered few advantages.

The economic imperatives of the Depression led to rules that allowed for the modern farm system. The major leagues had always resented being limited to the control of only 15 minor leaguers, but the minors liked it. The setup allowed minor league owners to control most of the best prospects and sell them to the major leagues for large prices once they were ready. The Depression, however, decimated minor league baseball–the number of leagues went from 25 to just 16 between 1929 and 1933–and the minors came to major leagues looking for financial relief. The major league owners agreed to invest in and help recapitalize minor league teams. In return, however, the major league owners demanded a rule change so that players on a minor league team controlled by a major league club no longer counted against the 40-man roster. Although the specific structure of the player control rules took several years to fully evolve, the new arrangement encouraged the development of the farm system as we know it today.

The Yankees were uniquely positioned to take advantage of this new environment. Like all capitalists, owner Jacob Ruppert saw his wealth severely curtailed in the economic downturn. But Ruppert had one unique advantage; he was a brewer, and with the repeal of prohibition in 1933, Rupert had an expanded and valuable source of income outside of his baseball franchise. Furthermore, unlike most other owners, Ruppert did not take distributions from his team’s profits; he reinvested them into the team.

Today the Yankee run from 1921 though 1964 is often remembered as one long dynasty. In realty it consisted of several distinct phases; one of the greatest began in the later years the Depression. Ruppert and general manager Ed Barrow quickly recognized the far-reaching impact of the new rules on minor league ownership and player control, and with Ruppert’s money built the best farm system in the American League. Supplemented with purchases of top minor league talent from many of the still independent minor league teams, the Yankees built one of the greatest sports dynasties of all-time. In the eight years from 1936 though 1943 New York won seven pennants and six World Series Championships and laid the groundwork for continued post-war success.

So what might the current economic downturn bring? Most obviously player salaries will stabilize or fall slightly as revenue falls off. So far, though, overall revenues have not declined. According to Forbes’ estimates, total baseball revenues actually increased from $5.5 billion in 2007 to $5.7 billion in 2008. Of course, the recession hit hardest in 2009, and those revenue figures are not yet available. Even if revenues fall slightly, however, it will not be enough to materially impact the structure of the game.

The largest impact may prove to be at the ownership level. Although team values have held up, the total wealth of many owners has been significantly reduced due plunging asset and hedge fund values. The baseball franchise itself, therefore, has become a greater proportion of the overall net worth of these owners. As their outside resources decline, they will have less financial flexibility to smooth out seasonal ups and downs in their team’s operational cash flow.

While baseball has always been subject to a diversity of wealth at the ownership level, the difference with this economic crisis is two fold: in the volatility of the relative wealth of the owners and in that market size will no longer be as important as ownership solvency. We have already begun to see this with Tom Hicks’ financial troubles in Texas and the Tribune Company’s bankruptcy in Chicago. The finances of both the Dodgers and Padres were recently thrown into confusion by the divorce proceedings of their principal owners. The fate of teams, and their willingness to spend on players, scouting, and marketing, is no longer as dependent on the fortunes of the team and its market size as on the changing economic circumstances of the owner.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.