For those of you sick of A.J. Burnett analysis, you have my sympathies, and please feel free to skip this post. For the masochists in the audience, I was inspired to take another spin down the Burnett freeway by our pal Brad Vietrogoski, who wrote a thought-provoking piece about everyone’s least-favorite Yankee on Tuesday. The following statement in particular caught my attention:

It’s not so much the two nasty curveballs that they swing and miss at in the at-bat that matter any more; it’s the fastball A.J. grooves with 2 strikes that they’re squaring up on and driving for power.

Having written about Burnett’s splits last month, I was curious to see whether the idea that Burnett was just laying it in there with two strikes held water.

A.J.’s tOPS+ (his performance relative to how he performs in all situations, with 100 being average and anything lower representing above-average for the pitcher) with two strikes last year was 36, while his tOPS+ while ahead in the count was 16, which means A.J. performed far better than normal in those situations. His sOPS+in each of those categories was 108 and 81, respectively, which means he was slightly worse than league average with two strikes in the count but almost 20% better when ahead. Essentially this tells me that it’s safe to say that A.J.’s issues last season weren’t necessarily grooving a fastball with two strikes.

However, he probably does have a sequencing issue, as evinced by his 208 tOPS+ when the batter is ahead in the count, and 157 sOPS+. While the 208 isn’t as crazy as it might initially seem, as we’d expect a pitcher to perform worse in favorable counts for the batter (for reference, CC Sabathia’s tOPS+ was a near-identical 206); the 57% worse than league average part is a bit more damning (CC’s was 111 in those situations).

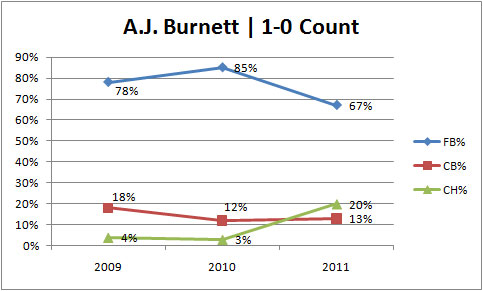

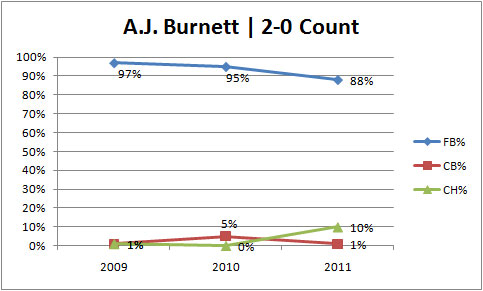

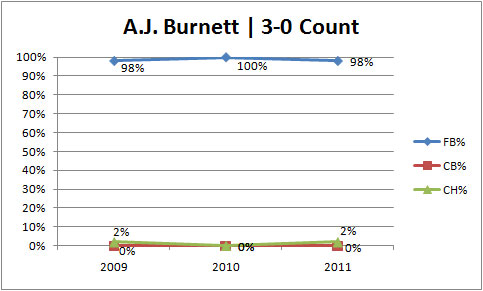

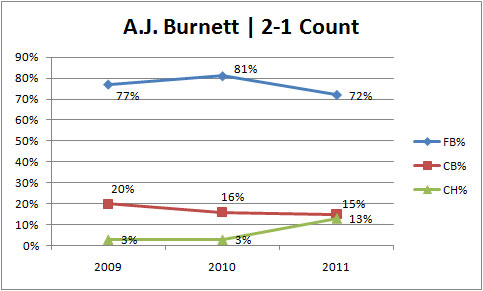

So what is A.J. throwing when falling behind in the count? The following splits are taken from Fangraphs — it’s important to note that these are BIS classifications and not PITCHf/x, and may not be exact, but they should be close enough for our purposes.

In 2011, he threw a three-year low percentage of fastballs in 1-0 counts, while his changeup percentage spiked from 3% all the way to 20%.

In 2011, he threw a three-year low percentage of fastballs in 1-0 counts, while his changeup percentage spiked from 3% all the way to 20%.

In 2-0 counts, A.J. decreased his fastball deployment to 88%, and went from throwing no changeups in this count in 2010 to 10% in 2011.

In 2-0 counts, A.J. decreased his fastball deployment to 88%, and went from throwing no changeups in this count in 2010 to 10% in 2011.

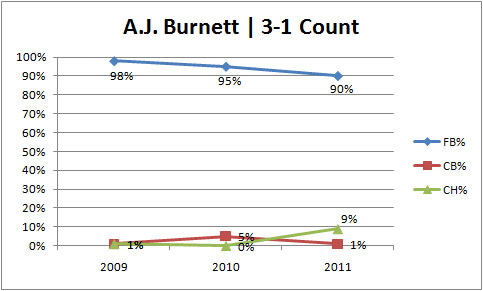

Getting a fastball from A.J. Burnett when ahead 3-0 is as sure a thing as there is in sports.

Getting a fastball from A.J. Burnett when ahead 3-0 is as sure a thing as there is in sports.

Again, a three-year-low in fastball%, while a spike in changeup deployment from 3% in 2010 to 13%.

Again, a three-year-low in fastball%, while a spike in changeup deployment from 3% in 2010 to 13%.

Pretty sure you see where I’m going with this by now.

Pretty sure you see where I’m going with this by now.

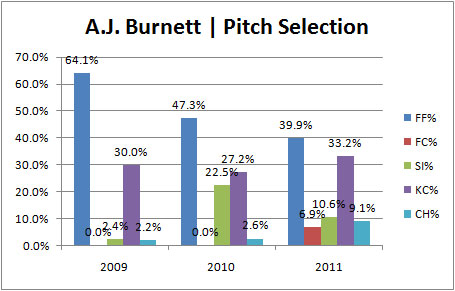

In 2011, A.J. Burnett decreased the percentage of fastballs he threw while upping his changeup percentage in every favorable hitter’s count. This unsurprisingly resulted in A.J. throwing more changeups overall last season than at any point in his three-year Yankee career (these are PITCHf/x classifications):

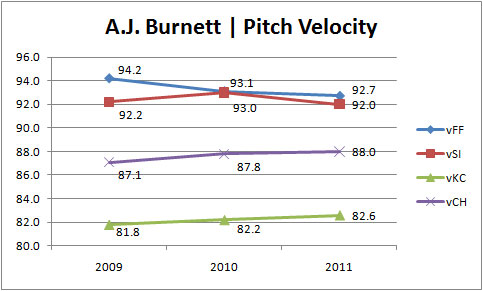

Why would he do this? Well, for starters, if you had the least-effective fastball in the American League, you’d probably stay away from it too. We’re all painfully aware of the diminished effectiveness of A.J.’s once-dominating heater.

Despite the drop in velocity, A.J.’s 2011 fastball still ranked as tied for the 15th-fastest in the game. Of course, it doesn’t matter how hard you throw if (a) you’re not getting any movement on it, (b) you don’t offer enough different looks to keep hitters guessing, and (c) all of the above. As far as (b) goes, to A.J.’s credit it appears he was toying with something of a cutter this past season, although it wasn’t exactly effective. He also appeared to have significantly cut back on sinker usage in favor of the change in 2011, though he barely threw either pitch in 2009.

Despite the drop in velocity, A.J.’s 2011 fastball still ranked as tied for the 15th-fastest in the game. Of course, it doesn’t matter how hard you throw if (a) you’re not getting any movement on it, (b) you don’t offer enough different looks to keep hitters guessing, and (c) all of the above. As far as (b) goes, to A.J.’s credit it appears he was toying with something of a cutter this past season, although it wasn’t exactly effective. He also appeared to have significantly cut back on sinker usage in favor of the change in 2011, though he barely threw either pitch in 2009.

While I commend A.J.’s appearing to be willing to try new things to right his ship, it’s pretty clear the change isn’t the answer for him, as its ineffectiveness (12th-worst in the AL) is likely tied in part to the fact that there’s just not enough separation in velocity from his heater. In 2009 the delta between his four-seamer and change was 7.2 miles per hour. In 2010 that shrunk to 5.3, and this past season it fell even further to 4.7.

So essentially in 2011, Burnett began turning to his changeup more frequently due in part to the decreased velocity on his fastball — this is not a terrible idea in theory; Mike Mussina for one had to reinvent himself as a pitcher as his velocity decreased near the end of his career — however, an inability to concurrently decrease the speed on his change resulted in what at times probably just looked like a slow, eminently hittable fastball. With hitters knowing full well that the likelihood of seeing a curve in a hitters’ count was slim to none, it’s sadly no surprise they teed off on Burnett’s changeup.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.