Everyone loves David Cone, at least I think everyone does. I’ve made it very well known that he’s my favorite YES announcer because of his affection for advanced stats, his candid stories, and because he occasionally talks before he thinks. He’s great. Cone sat down for an interview with Joe DeLessio of New York Magazine, and it truly is a must read. He discusses those advanced stats and his favorite sites, but also the Jorge Posada situation, the end of his own career, his involvement with the Stars and Stripes cap program, and much more. It gets RAB’s highest level of recommendation, so check it out.

RAB Live Chat

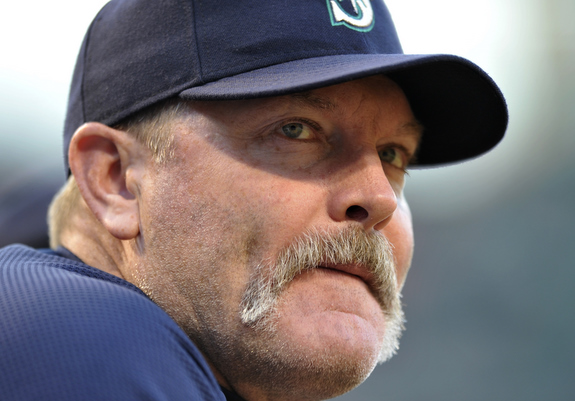

Series Preview: Seattle Mariners

The first of two west coast trips in 2011 starts in Seattle, which is universally considered one of the best road cities with a fantastic ballpark. I’ve never been there but I’ve heard it from plenty of people, so I’ll take their word for it. The Yankees won three of four in Safeco Field last season, losing only to the eventual Cy Young Award winner.

What Have The Mariners Done Lately

The Mariners come into this game having won eight of their last ten, though six of those wins came against the punchless Twins and Padres. They allowed just 17 runs in those ten games, and seven of them came in an extra innings win this past Monday. The latest hot stretch has Seattle’s season record at 24-25 with a -7 run differential.

Mariners On Offense

Last year, the Mariners featured the worst offense in the DH era, scoring only 513 runs in 162 games. They’re better than that this year, pushing 176 runs across the plate in 49 games, putting them on pace for 581 runs this season. Their best hitter this year, by far, has been Justin Smoak, the guy Jack Zduriencik wanted instead of Jesus Montero in the Cliff Lee trade. The switch-hitting first baseman leads the team in homers (six), OBP (.365), SLG (.461), ISO (.197), and wOBA (.363), and he recently graduated to the team’s full-time number three hitter.

The rest of the lineup just isn’t any good. Ichiro! sports a .281/.338/.320 line in his age 37 season, and chances are he’s declining instead of just slumping. Jack Cust still draws enough walks to post a good OBP (.364), but his power is gone (.091), he doesn’t hit for average (.231), and he strikes out at ton (35.7% of his at-bats). Chone Figgins has been the worst (qualified) hitter in baseball this season thanks to a .227 wOBA, though he’ll still steal on the rare occasions when he does get on base. Adam Kennedy (.332 wOBA) has been a nice surprise, but Miguel Olivo (.275 wOBA), Jack Wilson (.259 wOBA), Brendan Ryan (.296 wOBA), and Michael Saunders (.223 wOBA) have been predictably terrible. Franklin Gutierrez returned from a prolonged stomach issue not too long ago and has really to really settle in. The left field platoon of career minor leaguer Mike Wilson and prospect Carlos Peguero has yet to impress following Milton Bradley’s release.

Overall, it’s decidedly below-average offense with the second worst team wOBA (.286) and fourth worst OBP (.302) in all of baseball. Smoak is their one serious threat, but with all due respect, he’s not a Jose Bautista/Miguel Cabrera/Josh Hamilton kind of threat. There’s no reason to give him anything to hit in a big spot given his eight lineup-mates.

Mariners On The Mound

Friday, RHP Michael Pineda: They can’t hit, but they can certainly pitch. The 22-year-old Pineda is third in all of baseball (!!!) with a 2.25 FIP (only Roy Halladay and Matt Garza have been better) thanks to his 9.41 K/9 and 2.16 BB/9. The rookie right-hander is a big time fly ball pitcher though (just 34.7% grounders), and lefties give him a harder time than righties because he doesn’t have a changeup. Well, that’s a lie, he has one, but he only uses it 1.2% of the time. Pineda throws three different mid-90’s fastballs, though he uses the four-seamer (50.6% of the time) far more often than the two-seamer (10.8%) or changeup (5.6%). When he gets ahead, he’ll go to town with a mid-80’s slider in search of the strikeout. Being a fly ball pitcher plays into the Yankees’ hands and they can hit the fastball, but Pineda’s is so good that it might not matter.

Saturday, RHP Felix Hernandez: We all know about King Felix, who is probably the best right-handed pitcher in the world aside from Halladay. He’s actually been better this year than last (2.32 FIP vs. 3.04) even if he had a 4.33 ERA after four starts (he’s whittled that down to 3.01 in his seven starts since). The guy’s stuff is so good it’s scary. Felix throws two low-to-mid 90’s fastballs (four and two-seamer), a mid-80’s slider, a low-80’s curveball, and an upper-80’s changeup that is his favorite toy. Hernandez will throw anything in any count, so we just have to hope he has an off night, which is extremely unlikely.

Sunday, LHP Jason Vargas: The least known of the three, Vargas has gone from Marlins’ and Mets’ castoff to a rock solid starter. His 3.86 ERA is right in line with his 3.69 FIP, though he’s not a big strikeout (6.14 K/9) or ground ball (39.1%) guy. Vargas is a legit six pitch pitcher, throwing an upper-80’s two-seamer (30.1% of the time), low-80’s changeup (30.0%), mid-to-upper 80’s four-seamer (15.6%), mid-80’s cutter (11.2%), mid-70’s curveball (7.4%), and mid-80’s slider (5.7%). That unpredictability is why he succeeds with unspectacular stuff. Vargas has been very hit or miss this year, he’s allowed either five-plus runs or two or fewer runs in nine of his ten starts, so there really hasn’t been a middle ground.

Bullpen: As a whole, the Mariners’ relief corps is an unimpressive yet effective group. They don’t strike many batters out (6.09 K/9) or do a great job of limiting walks (3.60 BB/9), instead relying on a stout 50.4% ground ball rate to get outs. Closer and Michael Kay favorite Brandon League sports a 3.06 FIP and has fired off four scoreless appearances after allowing ten runs in three innings across four outings earlier this month. Eighth inning guy Jamey Wright (yes, that Jamey Wright) is striking out more than six men per nine while getting a ground ball on more than six out of every ten balls in play. Go figure.

Middle man David Pauley has a shiny 2.27 FIP, but that will change once his 0.00% HR/FB rate returns to Earth (48.6% grounders). Lefty Aaron Laffey isn’t a traditional specialist, instead working multiple innings to the tune of a 3.69 FIP. Jeff Gray was just claimed off waivers, and the final man in Seattle’s six pitcher bullpen is Yankees’ punching bag Chris Ray. Ah, we sure have some good memories of Chris Ray pitching against the Yankees, don’t we?

Recommended Mariners Reading: U.S.S. Mariner and Lookout Landing

Book Review: O Captain, my Captain

There is a book waiting to be written about the life and times of Derek Jeter. This book will explore what motivates him to excel on the field and how he behaves off the field where he was – and maybe still is – a king of New York’s social scene. In other words, it should delve into every aspect of Derek Jeter that makes him Derek Jeter. That book is not, however, Ian O’Connor’s highly anticipated biography The Captain: The Journey of Derek Jeter.

There is a book waiting to be written about the life and times of Derek Jeter. This book will explore what motivates him to excel on the field and how he behaves off the field where he was – and maybe still is – a king of New York’s social scene. In other words, it should delve into every aspect of Derek Jeter that makes him Derek Jeter. That book is not, however, Ian O’Connor’s highly anticipated biography The Captain: The Journey of Derek Jeter.

From the start, I knew that O’Connor’s book, at nearly 380 pages, would be a slog. The first sentence of chapter one read, “Like all good stories about a prince, this one starts in a castle.” That’s the way O’Connor has chosen to frame his biography. It’s not a critical look at Jeter; it’s not one with inside information about his social life; it excuses any short-comings; it is about a player O’Connor views as a prince.

After that, though, the book takes a turn for the better. The first 200 pages focus on Jeter’s background and early years with the Yankees. We learn about his grandfather’s youth in New Jersey as a foster child and how his work ethic shaped Jeter’s devotion to his eventual craft. We hear about the racial challenges Jeter’s parents faced as a mixed marriage at a time of less tolerance even in New Jersey and Michigan. We read about his youth as a start baseball and basketball player. As a scrawny teenager in the late 1980s, even then, Derek Jeter was destined for great things. He told his friends he would both be on the Yankees and date Mariah Carey, and everyone who knew him believed him.

As the tale progresses, O’Connor offers a glimpse back at the fateful draft of 1992. Somehow, Jeter, far and way the most productive player from that draft, fell all the way to the sixth pick. The Astros wanted Phil Nevin’s power while the Indians wanted Paul Shuey’s arm. The Reds’ advanced scouts and a young Jim Bowden urged the club to take Jeter with the fifth pick, but Julian Mock went the cheaper route. They picked Chad Mottola who appeared in just 59 games for the Reds, Blue Jays, Orioles and Marlins.

That draft was, of course, the first major turning point in Jeter’s life. He was expected to become the next great Yankee and had a signing bonus to match. He and Brien Taylor were due to lead the club into another era of greatness, but the game that came so easily to Jeter in Michigan proved challenging. At the age of 18, he hit .210/.311/.314 with 21 errors and would call home in tears every night. At age 19, his hitting improved, but he made 56 errors for Single A Greensboro. Already, Yankee officials were talking about moving Jeter out of short stop.

But as O’Connor notes, intangibles carried the day. Jeter, work ethic intact, turned himself into the sixth best prospect in baseball, and despite pressure from the front office to go with a more experienced short stop, he emerged as the team’s young spark plug in 1996. For his first five seasons, Jeter led a golden life. He won four World Series and dated Mariah Carey. After the 2000 World Series, Jeter was on top of the world, but even then, O’Connor had to position the second half of his book. “Derek Jeter, four-time champ,” he writes, “was the undisputed lord of the rings. He had no idea how much suffering he would endure in pursuit of his one for the thumb.”

The suffering, of course, came in the form of Those Other Guys. Once the synergistic energies of Paul O’Neill and Tino Martinez and Scott Brosius departed, the Yankees, says O’Connor, became a Me-First team. Jason Giambi, for instance, asked out of the 2003 World Series, much to Jeter’s chagrin. And then A-Rod arrives.

If this book has a villain, it is Alex Rodriguez. He’s the guy who kisses himself in the mirror, who slaps at baseballs, who cares too much about his image and manages to put his foot in his mouth. He’s the guy who dissed Jeter in an Esquire interview and who bears the full weight of the Yanks’ post-season failures from 2004-2007. He is the anti-Jeter, and this goes on for nearly 150 pages as O’Connor defines Jeter for what A-Rod isn’t as much as he does what the Yankees’ Captain is.

Using stories from Selena Roberts’ A-Rod expose and the Joe Torre/Tom Verducci memoir, O’Connor paints a familiar picture of A-Rod as a selfish guy. Perhaps that’s not an inaccurate picture of A-Rod, but he’s also a player who hit .303/.403/.573 with 173 home runs over his first four seasons in the Bronx. He certainly wasn’t embraced by Jeter who comes across as vindicative toward those who double-cross him, but he was a big part of the Yanks’ regular season success.

Eventually, Jeter and A-Rod reconcile as the Yanks’ Captain brings Alex “back into the fold.” He is embraced, and the Yankees win the 2009 World Series. It was Jeter’s crowning moment. “Jeter did not just embody the pride of the Yankees as much as any mythic figure before him,” O’Connor writes, returning to his favorite metaphor. “He proved a prince can become a king without lusting after the throne.” Mostly, the book is as saccharine and sterilized as it sounds.

Yet, buried within this tale of the prince of New York is something more interesting, and now and then, it shines through. While Jeter didn’t fully cooperate with O’Connor, he clearly gave his blessing for some of his closest friends — including Tino Martinez, David Cone and one-time Yankee farmhand R.D. Long — to sit with O’Connor. When they talk, Derek becomes more human and less princely. It slams the Mets for allowing the Baha Men to perform “Who Let the Dogs Out” before the 2000 World Series at Shea Stadium. He is absolutely frigid toward those who slight him or friends who do him wrong. He dumps Mariah Carey and kicks her to the curb with a brutal efficiency. He yells at Bernie Williams and Jay Witasick behind closed doors and is a far more vocal captain than many fans think. He parties as a youngster during Spring Training and courts starlets for decades.

To me, that’s what would make a Derek Jeter biography more interesting. It doesn’t have to be all wine and roses. We know about his on-field accomplishments; we have seen them day in and day out. But O’Connor’s book leaves Jeter’s private life well enough alone. The book rehashes the 2003 dispute with George Steinbrenner that eventually lead to an amusing VISA commercial and mentions Jeter’s extreme secrecy concerning the women he has dated. But Minka Kelly, for instance, is mentioned on a whopping six pages, and Joe Torre’s reluctance to push his favorite pupil to improve his defense gets very short shrift.

As an epilogue to the 2009 World Series, O’Connor provides some behind-the-scenes glimpses at Jeter’s contract negotiations, and here, the book does what I want to do. Jeter, painted as proud and not always receptive to criticism, did not take kindly to the Yanks’ suggestion that he wasn’t worth a nine-figure deal or $20 million a year. This is the excerpt that ESPN New York ran a few weeks ago as a teaser for the book. The Yanks pushed hard, and Jeter got upset. Eventually, Randy Levine settled the dispute by offering Jeter more money than he otherwise would have gotten and a player option, and everyone became friends — or at least frenemies — again.

Yet, even here, the book seems incomplete, and that’s because it is. Derek Jeter’s story is far from over. We have yet to see how Jeter, long accustomed to exploiting his natural talents to win World Series titles and not receptive to moving position, will respond to the inevitable and ongoing aging process. We don’t know what’s going to happen when he does have to move from short stop, and we haven’t seen how the Yankees and their fading star will address his anemic bat. That isn’t just an epilogue to the softcover edition of O’Connor’s book; it’s an entirely new section that can’t be written for years. We might know Jeter a little better after reading O’Connor’s biography, but Jeter might not know himself until he faces the adversity on the baseball field that inevitably comes with age.

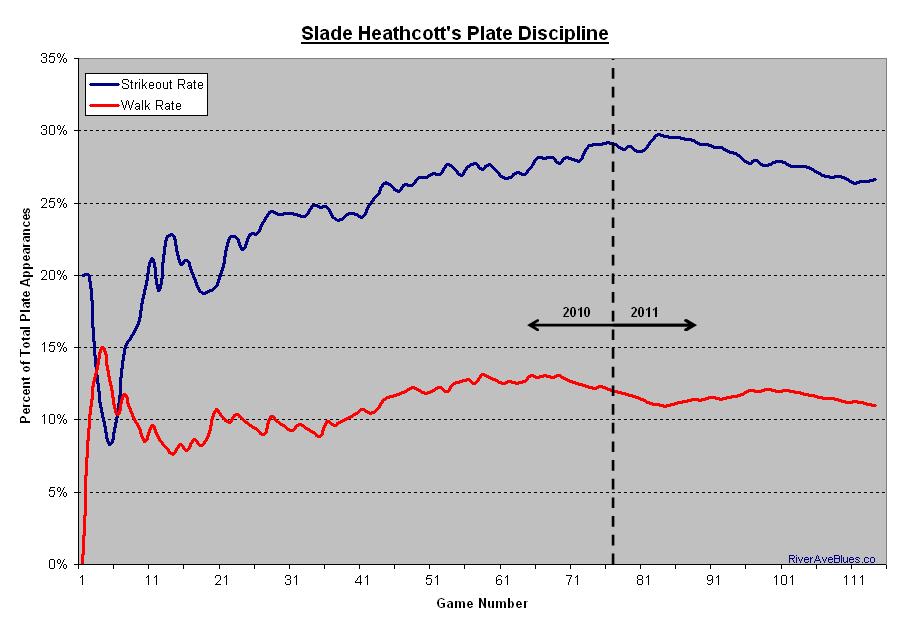

Graphing Slade Heathcott’s Plate Discipline

When the Yankees drafted Slade Heathcott in the first round of the 2009 draft, they knew he was going to be a bit of a long-term project. Just about every high school player is, unless you’re getting a rare talent like Alex Rodriguez or Jason Heyward or Rick Porcello or Clayton Kershaw. These kids need time to develop their physical tools into actual baseball skills, a process that tends to be more painful than pleasant. In 117 career games coming into Thursday, Heathcott is a .274/.363/.388 hitter with 140 strikeouts and 58 walks in 537 plate appearances. He’s been much more productive this year, with a .307/.382/.477 batting line in 38 games played. The hit tool – the ability to actually get the bat on the ball and drive it with authority – was never much of a question for Heathcott though.

The graph above shows Heathcott’s cumulative strikeout and walk rates (expressed as a percentage of his plate appearances) from the start of the 2010 season through Wednesday’s game. You can see that after joining the Low-A Charleston River Dogs in early-June last year, Slade’s strikeout rate gradually climbed as the season went on, finishing at 29.2% of his plate appearances. The walk rate also increased throughout the season, settling in at 12.1% on the final day of the year. That was the ninth best walk rate in the league (min. 350 PA) and the second best by a teenager, so yeah, be impressed.

Heathcott has gotten the strikeout rate under control in 2011 as he unsurprisingly repeats the league. After peaking at 29.7% of his career plate appearances seven games into this season, it’s dropped all the way down to 26.6% thanks to his last 31 games (just 15 K in 138 PA, or 10.9%). The walk rate has been up and down this season, but it’s generally hovered right around that 11-12% mark for his career to date. The walks aren’t a problem at all (league average is about 8.5%, both in Single-A and MLB) and the strikeouts are becoming less of one. The South Atlantic League average is 20.4% strikeouts (17.6% in MLB, if you’re wondering), and although Heathcott is still well-above that mark, he’s steadily improved this year, especially over the last month or so.

Note: Just to be clear, the graph does not include Heathcott’s three game came with the rookie level Gulf Coast League Yankees or Thursday night’s game. Those 15 or so plate appearances don’t make much of a difference anyway.

Montero, JoVa whiff four times each in SWB win

Update: The Low-A Charleston game is over and has been added to the post.

Apparently Andy Sisco has been released, I’m guessing to make room on the roster for Kanekoa Texeira. Sisco had a shiny 1.88 ERA, but the bottom line is that he’s a lefty specialist that walked eight and struck out just seven of the 32 left-handed batters he faced this year. You gotta do better than that when you’re fighting for a job.

Triple-A Scranton (5-0 win over Louisville)

Austin Krum, CF: 1 for 5, 2 K

Ramiro Pena, SS: 1 for 5, 1 R – singled off a brand name

Jesus Montero, C: 1 for 5, 4 K – apparently one of the strikeouts was a bad call

Jorge Vazquez, 1B: 1 for 5, 4 K

Justin Maxwell, LF: 2 for 4, 3 R, 1 2B, 1 RBI, 1 BB, 1 K – 14 K in his last nine games

Brandon Laird, 3B & Kevin Russo, 2B: both 2 for 5, 1 K – Laird doubled and drove in a run … Russo drove in two and stole a base

Dan Brewer, RF: 3 for 4, 1 R, 1 SB

Gus Molina, DH: 1 for 4, 1 2B, 1 RBI, 1 K

Carlos Silva, RHP: 7 IP, 4 H, 0 R, 0 ER, 2 BB, 3 K, 10-5 GB/FB – 56 of 91 pitches were strikes (61.5%) … very nice outing, though he’s probably going to have to do it once or twice more to convince the Yankees he’s better than what they have in their rotation right now

Eric Wordekemper, RHP: 0.1 IP, 1 H, 0 R, 0 ER, 0 BB, 0 K, 1-0 GB/FB – four of his seven pitches were strikes

Randy Flores, LHP: 0.1 IP, 1 H, 0 R, 0 ER, 0 BB, 0 K, 0-1 GB/FB – two of his three pitches were strikes

Kevin Whelan, RHP: 1.1 IP, 1 H, 0 R, 0 ER, 0 BB, 1 K, 2-0 GB/FB – eight of 11 pitches were strikes

Open Thread: New seat in the bullpen

So that thing’s new, eh? I noticed it for the first time two nights ago, but apparently the Yankees’ relievers have themselves a new elevated seat out in the bullpen. From what I remember, the guys just had to regular benches before that, not counting their little air-conditioned clubhouse in the back. This, ladies and gentlemen, is exactly the kind of hard-hitting analysis you’ve come to expect from RAB.

Anywho, here is tonight’s open thread. The Diamondbacks and Rockies (Micah Owings vs. Clayton Mortensen) will be on MLB Network, plus the Bulls and Heat will be on TNT a little bit later. Talk about whatever, go nuts.