A bit over twenty years ago, the San Diego Padres purchased the contract of Hideki Irabu from the Chiba Lotte Marines. There was no bidding process, nor was any other team able to offer Irabu a contract – the Padres were the early bird to the worm, and they stood to reap the rewards. This is noteworthy in and of itself, as it played a tremendous role in the creation and implementation of the posting system that we all know and loathe (though, to be fair, the system that brought Masahiro Tanaka over was an improvement, even if subsequent tweaks will prevent us from seeing Shohei Otani for a couple more years). But I digress.

The demand for Irabu was understandable. In addition to throwing the hardest recorded fastball in the history of the NPB (98 or 99 MPH, depending on the account), he was probably the league’s best pitcher from 1994 through 1996. Some called him the Japanese Nolan Ryan, while Bobby Valentine – a former manager – compared him to Roger Clemens (the 6’4″, 240 pound frame helped), and several scouts believed he would be better than Hideo Nomo. That last bit may not mean much nowadays, but it came on the heels of Nomo’s first two MLB seasons, which included a Rookie of the Year award, two Top-4 Cy Young finishes, over 10 K/9, a 133 ERA+, and 9-plus WAR (per both B-R and FanGraphs).

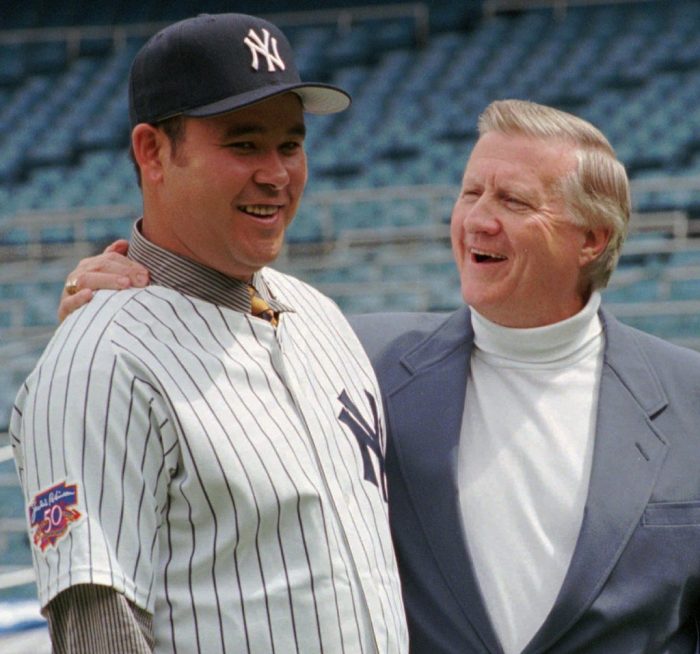

Unfortunately for the Padres (or fortunately, depending on how you want to weigh hindsight), Irabu refused to pitch in San Diego. He was a lifelong Yankees fan, after all, and that was the only organization that he would play for. And George Steinbrenner was more than happy to oblige, and a deal was struck. The Yankees sent top prospect Ruben Rivera (rated 9th overall by Baseball America a couple of months prior), Rafael Medina (64th on the same list), and $3 MM to the Padres, in exchange for Irabu, Homer Bush, and Gordie Amerson. They subsequently signed him to a four-year, $12.8 MM deal, with a team option for a fifth.

Fans, players, and talking heads the world over had strong opinions about the manner in which Irabu forced his way to the Yankees. A Tokyo-based newspaper was headlined “ARE YOU BLINDED BY MONEY?” on the heels of the deal, which is seemingly a timeless question for athletes. And both Andy Pettitte and Kenny Rogers questioned the signing, with the former griping about their comparative wages (Pettitte made around $600,000 in 1997). There was excitement, to be sure, but the skepticism and anger was palpable.

Irabu made his stateside debut shortly thereafter, making six warm-up starts in the minors. He dominated the competition, allowing a 2.32 ERA in 31 IP, and posting a ridiculous 34 strikeouts against just 1 walk. His fastball sat in the 94-96 MPH range, and his forkball had vicious bite in the upper-80s, low-90s. More than satisfied with his stuff and performance, the Yankees called him up to face the Tigers at home on July 10, 1997.

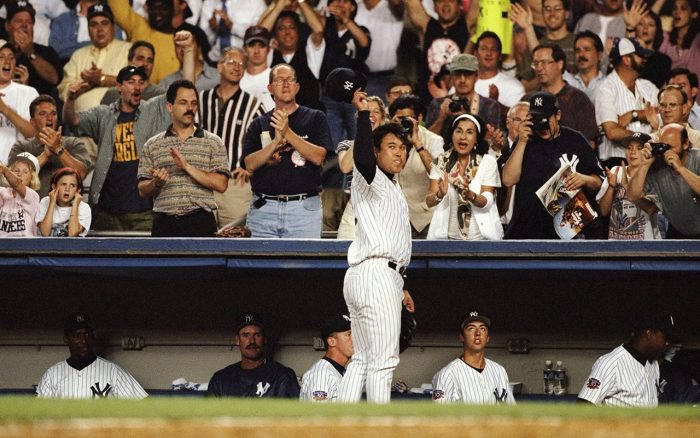

I was there that evening, as a part of a sell-out crowd (as compared to the average weekday audience of around 28,000), and I’m not sure that I’ve ever seen the stadium more excited for the first pitch of a relatively inconsequential game. That level of excitement was steady throughout the evening, with cheers at every strike and veritable roars with every punch out. When Joe Torre pulled Irabu in the top of the 7th the crowd reacted as though he had thrown a perfect game, demanding a curtain call. All told, he finished that night with 6.2 IP, 5 H, 2 R, 4 BB, and 9 K. It was a fine debut, and it seemed as though a legend was being born.

The brakes were pumped in short order, though, as Irabu was awful over his next seven starts, earning a demotion to the minors and a return engagement in the bullpen. In the eleven appearances between his first and last starts of the season, batters hit .343/.395/.663 against Irabu, which led to an 8.42 ERA in 41.2 IP. The first uses of ‘I-Rob-U’ were born during this stretch, as fans turned on him rather quickly. Some faint glimmer hope was found in his final start of the season, against those same Tigers, when he went 5 IP, allowing just 2 hits, 1 run, and no walks, while striking out 6. The final line was ugly – a 7.09 ERA and -0.9 bWAR in 53.1 IP – but there were flashes of brilliance sprinkled in.

That glimmer of hope expanded tenfold in the first few months of the 1998 season. Irabu allowed 1 run or less in six of his first seven starts, and boasted a 1.13 ERA in 47.2 IP when Memorial Day rolled around. When the first half came to a close, he was sitting on the following line: 86.2 IP, 67 H, 40 BB, 65 K, 2.91 ERA. The strikeouts and walks weren’t terribly strong, but we were at the tail end of the dark days of baseball analytics, and that ERA was quite good in the run environment of 1998. The wheels fell off in the second half, to the tune of a 5.21 ERA in 86.1 IP, and Irabu didn’t factor into the 1998 playoffs.

Overall, 1998 wasn’t a terrible year for Irabu. Disappointing? Sure. But 173 IP of 109 ERA+ ball isn’t too shabby, and he actually bested Pettitte in H/9, K/9, ERA+, and bWAR. The sequencing of it all kept him off of the playoff roster (as it should have, as he was all but unpitchable down the stretch) – but there were still some signs that he could be a competent back of the rotation starter. And, given his contract, he’d get the chance to be just that.

Instead, Irabu was viewed as a dead man walking in 1999, his season tarnished by Steinbrenner referring to him as a “fat pussy toad” after he failed to cover first in a Spring Training game. (Pussy as in full of pus.) He was sent to the bullpen to open the season, spending the entirety of April as a mop-up reliever, before rejoining the rotation in May. The writing was on the wall at that point, it seemed, and Irabu did little to help his cause. His strikeout and walk rates improved markedly over his 1998 season, and he looked quite good in June (3.33 ERA in 24.1 IP) and July (2.64 ERA and 4.1 K/BB in 44.1 IP) – but that represented the high point to an otherwise dreadful season, including two-plus awful months to close the season (6.63 ERA between August and October).

The Yankees officially gave up on Irabu thereafter, and he was dealt to the Expos for Jake Westbrook, Ted Lilly, and Christian Parker in the 1999-2000 off-season. He spent three more years in the majors (two in Montreal, one in Texas), battling injuries, ineffectiveness, and demotions to the minors, throwing his last big league pitch on July 12, 2002 … he allowed a walk-off single to Jacque Jones in a 4-3 loss to the Twins.

Irabu finished his career with 514 IP across 126 appearances (80 starts), posting a 5.15 ERA (4.97 FIP) along the way. His 18.1% strikeout rate and 7.8% walk rate were both better than average for their time, but his propensity for the long ball (1.59 HR/9 for his career) and gradually increasing hittability felled him. Luckily for the Yankees, their return for Irabu was much better than what they gave up back in 1997 – and he didn’t stop them from winning back-to-back World Series championships.

He returned to the NPB in 2003 at 34-years-old, pitching for the Hanshin Tigers of the Central League (in a rotation with Kei Igawa, because of course). He finished fourth in the Central League with 164 strikeouts, with a league-average-ish 3.85 ERA. He attempted a return engagement in 2004, but injuries essentially ended his career.

Irabu’s post playing days were discussed quite a bit when he committed suicide in 2011, and they don’t bear repeating here. Despite his struggles with the Yankees, I remember him somewhat fondly. He started one of the most exciting games that I’ve ever attended (I was eleven at the time), and his forkball stands out as one of the first filthy breaking balls in my memory. His career was a disappointment, and much of it was a circus – but the talent was there, and he was fun to watch when he was right.

If you’d like to take a few moments to see what could have been, I recommend these two videos. The first is from 1994, when he was still pitching in the NPB:

And the other is from his MLB debut: