What makes a baseball player gritty? Is it tenacity? Work ethic? Selflessness? Bravado? Or is it something more tangible, like whiteness. We can presume that having grit will improve one’s chances of scoring a date with a woman with Misty or Dawn or Misty-Dawn in her name. But does having a surplus of it make for a qualitatively better ballplayer? These stubborn questions have pitted baseball fans against each other and have only intensified since the dawn of advanced statistics, when it was revealed that virtually all players with a Fu-Manchu, stirrup socks, or a propensity for bunting every third at-bat were perhaps not as good as advertised.

In fact, it wasn’t until 2007 that MLB commissioner Bud Selig, after an intense barrage of e-mails from the stat-minded segment of the baseball community, finally replaced former Phillies second baseman Mickey Morandini on the All-Century Team with Lou Gehrig, in a posthumous nod to the venerable Yankee. During the 2008 World Series, you might recall that Selig alienated even more people by issuing an awkward half-apology while interviewed by Fox’s Tim McCarver on national TV:

Don’t get me wrong, Gehrig was good. But Morandini was like a welterweight out there, mixing it up – scrapping, hustling, spitting chew, telling people what’s what, and laying down bunt after bunt after bunt. And you wanna’ talk heady? Who else would have the presence of mind to lay down a sac bunt with his team down eight runs or more. Mickey Morandini – fourteen times. But that Gehrig: he was certainly a true Yankee.

Part of what makes the concept of grit so polarizing is its favorable reputation among baseball people who still covet the more intangible elements of the game. In this context, a player who would otherwise get traded or cut for putting up substandard advanced stats like OPS+ or WARP 3 can add years to his Major League career based on an interminable scowl or an uncanny talent for somehow finishing every contest with splotches of blood on his uniform, even in games when he doesn’t play.

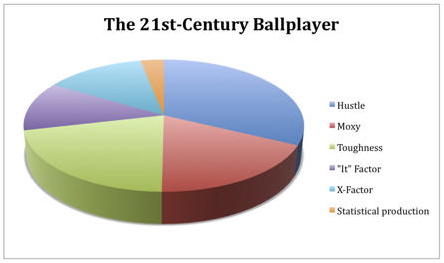

The defining moment of the grit controversy occurred in 1996, when Sports Illustrated ran a cover story entitled “The 21st-century ballplayer.” In the piece, which is accompanied by a now famously incendiary pie chart, baseball beat writer Dave Ballaster celebrates the grittiness of the next generation of ballplayer while railing against excess and greed. Here’s an excerpt, per the S.I. archives, along with the graph:

Jaded fans and diminished ticket sales will mean fewer teams, less room for pretenders, and more competition among remaining big-leaguers. In other words, the 21st-century ballplayer will be of tougher, grittier stock and attitude. And it will be a welcome change. Gone from the baseball diamond will be the gold-chain-wearing, Crystal-swilling, diamond-earring-having, seven-figure-earning prima donnas. A new breed of heartier, headier ballplayer will emerge. He’ll slash at an outside pitch instead of waiting for a free pass and seethe when his line drive clears the outfield wall because he won’t have had the chance to stretch a double into a triple. He’ll have convictions, an unsinkable work ethic, longevity and, yes, even a grunginess about him: Think Temple of the Dog, not ‘N Sync; Seven Mary Three, not Ace of Base. They will be throwbacks, to be sure; and here’s what they will be made of:

The saber community revolted; understandably, talk of quantifying a player’s instinct and resiliency vanished. But the real truth was, there just weren’t any tools available at the time that could accurately measure such a nebulous thing. Until now, that is. Enter the newest advanced baseball metric: GRIT capacity.

GRIT is an acronym for Guts, Resolve, Instinct, and Toughness, and was devised by a team of aerospace engineers at NASA when the question arose of which baseball player would be most able to endure the 20 G centrifuge without fainting, power-vomiting, or sobbing uncontrollably. And as for their unanimous answer? Ty Wigginton.

Before I get into the specifics of GRIT, it’s probably important to note that it’s taken some heat lately from sabermatricians. Tom Tango, for example, referred to the advent of GRIT in one of his more recent blog posts as “what would happen if Bill James lost everything, went on a smack binge, and found himself tattooed and naked, at 3 A.M., at the bottom of a Wendy’s dumpster in Bakersfield.” I disagree. Though imperfect, like every advanced stat, GRIT has its utility, providing it’s used in the right context. For example, knowing the overall GRIT capacity of a player can help a manager decide whether or not to play him in centerfield at Wrigley, lest a deep fly ball inspire him to dive face-first into a solid brick edifice.

At its essence, GRIT is a weighted measurement that attempts to accurately assess the overall nature and value of an individual player’s soul, which goes a long way in determining whether or not he would make for a winning teammate. In going about this process, GRIT accounts for aspects of that player’s work ethic, mental toughness, physical resiliency and life philosophy – qualities that are gauged through subjective observation, preconceived notions, and statistics that have, for the most part, fallen out of favor – and then scales them to the venue in which he plays. The ballpark adjustment is necessary because it accounts for individuals who play their home games in stadiums with domes or retractable roofs; it stands to reason that few factors can adversely impact a player’s favorable GRIT capacity as rapidly as a spotless uniform and climate control.

It should be pointed out that GRIT capacity is the only current metric that assesses these dimensions of a player by using an all-inclusive formula. A team version of GRIT (tGRIT) also exists, but for now we’ll focus primarily on the individual player version: As you’ll soon see, things can get pretty complex in a hurry. With that said, don’t let the intricacies intimidate you. While all of the moving parts may seem daunting at first, any numerical miscalculations made in arriving at a player’s GRIT can be easily overridden by one’s gut instinct, personal biases, or mood

Tomorrow, we’ll set off on our pursuit of one particular player’s GRIT capacity by isolating each of the metric’s primary components, starting with guts. We’ll also ponder a very real question that continues to divide fans: Does GRIT transfer to good?