The Core Four as we know it did not become the Core Four until 1998. Derek Jeter, Andy Pettitte, and Mariano Rivera were all established big league stars who’d helped the Yankees win a World Series by time that 1998 season rolled around. They were the present and the future. In 1998, it was Jorge Posada’s turn to join the mix.

* * *

Posada had cups of coffee with the Yankees in 1995 and 1996 — he was on the 1995 ALDS roster as a pinch-runner, if you can believe that — before spending the 1997 season as Joe Girardi’s backup. He started 52 games that year and hit .250/.359/.410 (101 OPS+) with six homers and nearly as many walks (30) as strikeouts (33). It was a damn fine first full MLB season. The only problem? Posada was 26 and growing impatient.

“They keep saying I’m the catcher of the future. For me, the future is now,” said Posada to Jack Curry in January 1998. “I’ve been working hard all these years to win the job. My time is now. I don’t want to be too late. I’m going to be 27 in August. They keep saying I’m the future. By the time I get there, it’s going to be too late.”

Although he was a 24th round draft pick who never appeared on a Baseball America top 100 prospects list, Posada was not an unknown. He was a well-regarded prospect who ripped up Triple-A — Jorge hit .271/.405/.460 with 11 home runs in 106 games with Columbus in 1996 — and had been asked about during trade talks. Posada to the Padres for Rickey Henderson was a popular rumor at the 1997 trade deadline.

GM Bob Watson had no real interest in trading Posada. It was all George Steinbrenner. Girardi was entering his mid-30s and Watson saw Posada as the heir apparent. The Yankees even left Girardi unprotected during the November 1997 expansion draft. Both the Diamondbacks and Devil Rays passed, however. Girardi knew his days as a starter with the Yankees were numbered. Posada’s ability was obvious.

“One thing (Girardi) told me was, ‘I’m holding the job for you,'” said Posada to Curry. “I’ll never forget that. He knows what’s going on. He’s been a friend and he’s helped me a lot. He’s still going to help me, no matter if I’m starting or not. He’s not jealous about me playing, and I’m not jealous about him playing.”

* * *

When the season started, it was Girardi behind the plate on Opening Day, not Posada. And in the second game of the season too. And the third. Posada didn’t get his first start of 1998 until April 5th, the fourth game of the season, and he responded by going 3-for-5 with an eighth inning go-ahead two-run home run against the Athletics. Posada later scored the go-ahead run in the tenth inning after Rivera blew the save.

Posada started again two days later and hit another home run. For the first few weeks of the season, he and Girardi split catching duties 50-50 — they both started 16 of the first 32 games of the season — which was an increase over Posada’s workload in 1997. On May 17th, Jorge was behind the plate for David Wells’ perfect game, baseball’s first perfect game in four years and at the time only the second by a Yankee, after Don Larsen in the 1956 World Series.

By time Wells threw his perfect game, the Yankees were locked in and emerging as baseball’s powerhouse. The perfect game was their 28th win in the span of 34 games. The Girardi-Posada timeshare behind the plate was working, so why fix what’s broken? That’s the approach Joe Torre took. The two continued to split time 50-50.

“Jorge’s chances of getting better have improved only because of (Girardi’s) attitude,” said Torre to Claire Smith. “He doesn’t have blinders on. He knows that Jorge is the future catcher in this organization. But he’s going to do whatever he can to help us win, to help this kid develop.”

When the All-Star break rolled around, the Yankees were 61-20 and had lost nine fewer games than any other team in baseball. Posada started 44 of those 81 first half games. Girardi started the other 37. Their first half batting lines:

- Posada: .275/.374/.479 (126 OPS+) with eight home runs

- Girardi: .248/.310/.346 (75 OPS+) with two home runs

Posada also had more success throwing out baserunners (40%) than Girardi (26%). There is something to be said for veteran leadership, no doubt, but halfway through the 1998 season, it had become clear the Yankees were a better team with Posada behind the plate, not Girardi. Besides, Jorge caught Andy Pettitte in the minors and had taken over as Orlando Hernandez’s personal catcher, and he caught Wells’ perfect game. He handled the pitching staff just fine.

It wasn’t until the end of July that the 50-50 timeshare behind the plate came to an end. Girardi started 12 of the first 21 games after the All-Star break. Posada then started 37 of the final 60 games of the season. He finished the year with a .268/.350/.475 (115 OPS+) batting line and 17 home runs in his 83 starts. Girardi hit .276/.317/.386 (75 OPS+) with three home runs. The 27-year-old switch-hitter with power had taken the job from the 33-year-old defensive specialist.

“I’m able to be realistic and understand the situation,” said Girardi to Smith. “(Being upset) doesn’t help anyone. I don’t believe it helps yourself — and I think that’s why guys try to be a problem, to help themselves. Most of all, I think it hurts the team. And this is a team sport. Jorge is very easy to work with. He’s a good kid. He wants to learn. He wants to get better.

”He’s also very beneficial to this team, a team that has a chance to go to the World Series,” Girardi added. “As you get to be 33, 34, you don’t know how many more shots you’ve got. The games are long when you’re on the bench, but from that standpoint, I think I’m able to be realistic and get the best out of the days that I’m playing. That’s all I can do.”

* * *

In the postseason, rather than play Posada behind the plate every game, Torre came up with a personal catcher system. Posada caught Wells and El Duque while Girardi caught Pettitte and David Cone. Torre didn’t deviate from the plan at all. Wells started Game One of the ALDS against the Rangers and Posada was behind the plate. Girardi caught Pettitte and Cone in Games Two and Three, respectively.

Posada caught Wells in Game One of the ALCS against the Indians, Girardi caught Cone in Game Two and Pettitte in Game Three, Posada caught Hernandez in Game Four and Wells in Game Five, and Girardi caught Cone in Game Six. Through the ALCS, Posada was 2-for-13 (.154) with a home run, five walks, and four strikeouts in the postseason. Girardi was 5-for-15 (.333) with one walk and one strikeout.

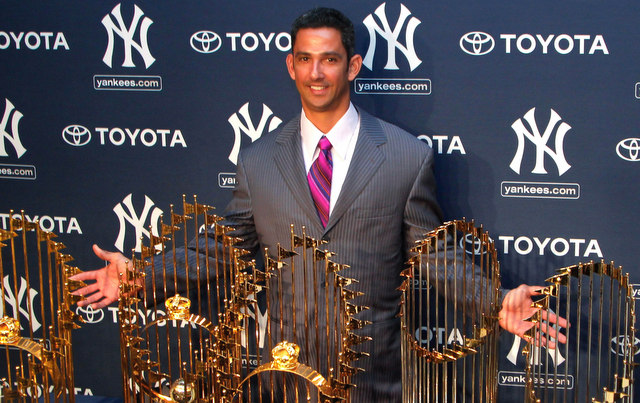

The personal catcher system got the Yankees to the World Series, so there was Posada behind the plate for Wells in Game One and El Duque in Game Two against the Padres. Girardi caught Cone in Game Three and Pettitte in Game Four to complete the sweep. He went 0-for-6 in the World Series. Posada went 3-for-9 (.333) with two walks and a home run in the blowout Game Two win.

It seemed obvious the Yankees would part ways with Girardi after the season and commit to Posada as the full-time catcher going forward, but that didn’t happen. Well, the second part happened. Posada did take over as the clear cut starter in 1999. But Girardi stuck around. The Yankees picked up his $3.4M option.

“At a time when quality catching is at a premium, Joe Girardi is one of the best defensive catchers in baseball and Jorge Posada is one of the game’s emerging stars at that position,” said Brian Cashman to Buster Olney in November 1998. “You also cannot overstate Joe’s leadership abilities.”

It had been previously announced the Yankees would decline Girardi’s option — Girardi even said he understood the decision and would look for a starting job elsewhere — but Torre reportedly lobbied Cashman and George Steinbrenner to keep Girardi because he valued his leadership and the way he worked with Posada. Girardi knew Posada was there to take his job. He mentored him anyway.

“It’s not easy to compete with him because he’s such a nice person,” Posada said to Smith. “Ever since I got here he’s gone out of his way to help me, to tell me about how to call games, to tell me about the league. I’ve got nothing but admiration for him.”